Photo: Tenzin Tsundue / Facebook

Tenzin Tsundue, the writer and activist, is on the last leg of his three-month journey along the Tibetan border with India, from Ladakh to Arunachala Pradesh. He set out on August 17, walking and using local transport saying, “Chinese aggression on the borders has left people in the Himalayas shocked and worried […] Tibet’s independence is in the long term interest of India, how long can India suffer China?”

He is now in Arunachal Pradesh, where he was interviewed on arrival by Tawang News, Tawang’s main TV channel. He has passed through Himachal Pradesh, Uttrakhand, Lucknow, Banares, Patna and Siliguri. He visited Kalimpong, Darjeeling and nearby areas, and toured different parts of Sikkim before arriving in Arunachal Pradesh.

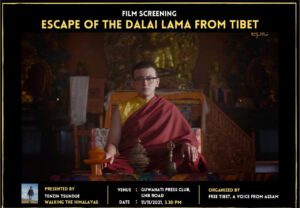

Tsundue has held press conferences, creative writing workshops, screenings of the film Escape of the Dalai Lama from Tibet in Hindi, and spoken to thousands of people along the way, from people on the street to audiences in large venues, to schools, to poetry readings in cafés, spreading the message about the strategic importance of Tibet to India. He says his plan was to “journey through the five Indian Himalayan states to create more awareness about the 70 years of Chinese occupation of Tibet and its impact on the Indian Himalayas, and also the growing Chinese security threats to India”.

The film, which he has screened over 80 times during his journey, has made it possible, he says, for him to “connect with the Himalayan Indians on the issues of language, culture and the people to people relationships, stories of old trade routes, customs and marriages. Although the government and the Indian Army are doing everything necessary I observed on this journey that the common people in the border areas have little to no awareness about China’s expansionist policies and its current activities in the borders”. He says that his audiences have been “deeply touched” by the film, and that people in Spiti and Kinnaur said that the Dalai Lama’s presence in India has helped them keep their language, culture and religion alive.

The film, which he has screened over 80 times during his journey, has made it possible, he says, for him to “connect with the Himalayan Indians on the issues of language, culture and the people to people relationships, stories of old trade routes, customs and marriages. Although the government and the Indian Army are doing everything necessary I observed on this journey that the common people in the border areas have little to no awareness about China’s expansionist policies and its current activities in the borders”. He says that his audiences have been “deeply touched” by the film, and that people in Spiti and Kinnaur said that the Dalai Lama’s presence in India has helped them keep their language, culture and religion alive.

Tsundue’s account of his journey, spread through his Facebook page, includes anecdotes he has picked up along the way. In Darjeeling, he said that “the name Darjeeling itself, which has become an inimitable brand, has historically a Tibetan origin. The name Dorje Ling, meaning land of ‘Dorjee’ or thunderbolt became anglicised into ‘Darjeeling’.” He tells of another “good local source” saying that it was named after the Tibetan Buddhist guru Terton Sogyal Dorjeelingpa who stayed on the hills once.

Tsundue’s account of his journey, spread through his Facebook page, includes anecdotes he has picked up along the way. In Darjeeling, he said that “the name Darjeeling itself, which has become an inimitable brand, has historically a Tibetan origin. The name Dorje Ling, meaning land of ‘Dorjee’ or thunderbolt became anglicised into ‘Darjeeling’.” He tells of another “good local source” saying that it was named after the Tibetan Buddhist guru Terton Sogyal Dorjeelingpa who stayed on the hills once.

Tsundue goes on to tell of Darjeeling being the asylum for the previous Dalai Lama, the Great Thirteenth, and that the refugee centre has erected a statue to commemorate his exile abode. And not far from Darjeeling is Mané Banjang, a small border village between Nepal and India where he describes a 40 km stretch as “one of the most dangerous routes I have ever seen, the broken asphalt road relentlessly rises up steep like a gyre to heaven, making the ascent incredibly risky […] some places like Guras, Tumling, and Chitrey fall in Nepal territory which has small and scattered Tibetan communities still living there on almost noman’s land”.

Photo: Facebook

Arriving in Ravangla, near Namchi, “We went straight to the town to set up the film screening” where they met opposition. “A local sub district officer suddenly conjured up an ‘international controversy’ around the Dalai Lama film we had been screening for 70 days all across the Himalayas, and disallowed it. We had to go back to our Tibetan refugee camp and quickly put together the show, then we realised the refugees had no proper electricity and we had to work in dark […] using our phone lights. We had to arrange a long wire to bring in electricity connection from the nearby army cantonment. By the time the guests poured in from Ravangla town, including the Member of the Legislative Assembly we were ready. We had a big show for about 200 people.”

At every step of the way he pays tribute to the people who helped with organisation and set up, many Tibetans stepped up, and worked together with Indian friends to ensure the success of the trip, and to the goodwill and encouragement he received along the way.

The publicity on his journey has enabled him to voice his message to large audiences through the media of television, radio and newspapers, as well as his huge following on social media.

* You can follow Tenzin Tsundue’s journey through his Facebook page.

Print

Print Email

Email