While for foreign tourists getting into Tibet is almost as hard as North Korea, Chinese visitors are flooding into the country in droves.

The Chinese government says 23 million people will enter the Tibetan Autonomous Region this year,an area with a permanent population of just 3.2 million. The figures are suspicious to say the least – it would mean 63,000 people entering the area every day – but accurate or not, numbers are on the rise. In the decade since a train route was opened across the high-altitude plateau, Tibet has seen an 11-fold increase in visitors.

And the country has been made ready for them. Tibetan villages like Zhaxigang in the south-east of the country have been bulldozed, replaced with houses built by Chinese real estate developers. They are picture perfect replicas of the homes that used to stand there. Tibetans who lost their homes will be given new accommodation, officials have said but their opportunities to make money may be limited. Restaurants in a nearby site are overwhelmingly run by Han Chinese.

Large areas of Lhasa to look like any modern Chinese city these days, with hundreds of old buildings knocked down to make way for shopping malls, restaurants and modern blocks of flats. It already boasts an Intercontinental Hotel as well as a Sheraton, a St. Regis and a Shangri-La, and officials predict 10 more luxury hotels there by 2020.

The Chinese government is investing heavily, enthusiastically promoting tourism as a pillar of the economy with hopes that it will soon become a world class holiday destination. “It is the new engine for development in Tibet,” Penpa Tashi, vice chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region told reporters shortly before the opening ceremony of the Third China Tibet Tourism and Culture Expo in Lhasa.

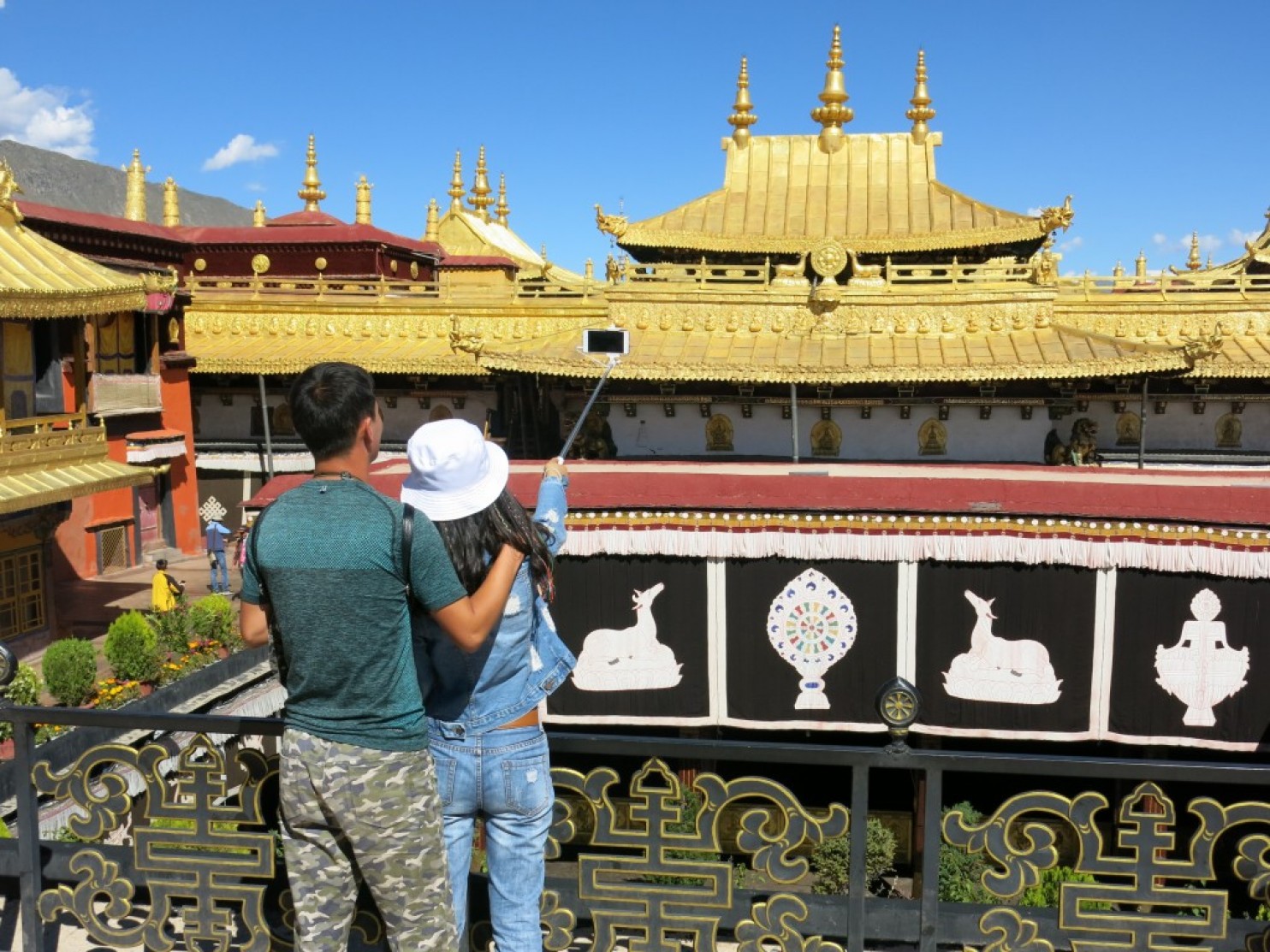

Tourism already makes up one-fifth of the economy of the Tibetan Autonomous Region, has created 320,000 jobs and is helping to fuel double-digit rates of growth, officials say but critics argue that Tibetan culture is being destroyed, its environment ruined and its holy sites overwhelmed by Chinese tourists.

Elliot Sperling, an Indiana University professor says China has a narrow, materialist view of development as the solution to all Tibet’s problems, and warned that tourism risks turning parts of the country into a “Lama Disneyland.”

“Lhasa has been turned from a holy place of pilgrimage into a tourist site,” said Tibetan writer Woeser who last visited the city three years ago. “Most tourist shops in the Tibetan old town are owned by Han Chinese and many supposedly Tibetan artefacts are manufactured in other parts of China.”

Professor Christiaan Krieger has likened the changes to how the United States treated its developing West 100 years ago. “They are commodifying the native people,” she stated, “bringing them out as an ethnic display for the consumption of people back east.”

If the tourism industry continues to grow at this rate, more people from mainland China – keen to profit from visitors – will move to the region permanently and the relatively small Tibetan population will become increasingly marginalised.

Some Tibetans do benefit from tourism: many tour agencies run by locals have opened in recent years and Wang Songping, deputy director of the Tibet Tourism Development Commission maintains that the industry has both positive and negative effects everywhere in the world. The influx of money will encourage people to protect “their intangible cultural heritage,” he argues.

But in the vast majority of cases, critics say, Tibetans are neither consulted nor empowered as their land is transformed. The top jobs and most of the profits are being monopolised by companies and people from elsewhere in China, fuelling the kind of resentment that contributed to the riots across the country in 2008.

Print

Print Email

Email