In a landmark move, the Election Commission (EC) of India has ordered State Commissions to include all people of Tibetan origin born in India between 1950 and 1987 on the electoral rolls. This entitles the children of Tibetan refugees who were born between those dates the power to vote for the first time. The move comes in time to enable them to vote in the upcoming elections, but has received mixed reactions from the Tibetan community.

It is thought there are around 120,000 Tibetans living in India, of whom around 48,000 are now eligible to vote.

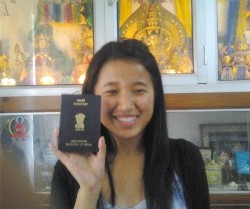

The debate began in 2010 when Namgyal Dolkar Lhagyari, who was born in India in 1986, was denied a passport. She went on to file a case in the Delhi High Court challenging the denial. The ruling in December 2011 reminded the government that all people born in India before July 1987 are regarded as Indian citizens. A Karnataka High Court confirmed this ruling in a similar case in August 2013.

The Delhi High Court declared Namgyal Dolkar Lhagyari an Indian citizen by birth and issued her an Indian passport in December 2010.

Photo: Phayul

The Citizenship Act of 1955 was amended in 1986 and removed the citizenship right conferred to any foreigner born in India. But it was not applied retrospectively and therefore foreigners who were born in India before 1987 would still be regarded as the citizens of this country. “We are only implementing existing court orders” said Deputy Election Commission Alok Shukla “Only Indian citizens have voting rights in India. Who is considered a citizen is a matter of adjudication.

Some Tibetans living in exile feel that this will derail their fight for Tibet.

The Tibetan government-in-exile has stated that it would not prevent Tibetans from seeking Indian citizenship – a change from their previous policy that Tibetans should retain their status of “stateless” refugees. Karma Yeshi, a member of Tibetan Parliament, said, “Our aim is not to settle in India, but to eventually go back to Tibet.”

Tibetans who remain refugees are eligible for some benefits, but some claim that the value of these is less than those conferred by citizenship. Many people welcome the new ruling, citing the advantages that would come with citizenship which include more jobs and the freedom to travel anywhere around the country. “At present, Tibetans can only work in the private sector… at places like call centres,” says Shibayan Raha, a former Grassroots director for Students for a Free Tibet. “They have to pay higher fees at university. This move will entitle them to benefits such as government jobs and less harassment by officials.”

Tibetans are free to retain their identity and continue living in India in exile while fighting for the Tibetan cause. If they wish to file for Indian citizenship, they need to apply for the official papers. Alok Shukla of the Election Commission added that only when someone wants to get enrolled on the voter list, do they have to categorically state that they are citizens of India. Until then, they need not clarify anything.

March 27 Update

The Union Home Ministry has decided to challenge the issue of voting rights for Tibetan refugees. Security agencies have red-flagged the issue, saying it raises important international strategic and security considerations and that it could have a serious impact on diplomatic ties with China. The Home Ministry is to file a special plaint in the Supreme Court challenging the High Court order.

If Tibetans can vote it would be likely to affect the outcome of Lok Sabha polls in parliamentary constituencies with a large population of Tibetan refugees, particularly Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, Gangtok in Sikkim, Dharamsala in Himachal Pradesh, Shillong in Meghalaya and Mysore in Karnataka.

Print

Print Email

Email