In recent months, a number of former detainees from Chinese forced labour camps have come forward to recount their experiences of human rights abuses at the hands of the authorities.

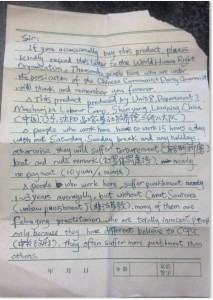

The first case that drew international attention to the conditions within the camps came in October last year, when Julie Keith, an American woman from Oregon, found a hand-written note in the Halloween box-set she had bought in her local Wal-Mart. The note detailed how the writer and fellow inmates, imprisoned at the Masanjia labour camp in Northeast China, toiled seven days a week, their 15-hour days haunted by sadistic guards. “Sir: If you occasionally buy this product, please kindly resend this letter to the World Human Right Organization,” said the note, “Thousands people here who are under the persecution of the Chinese Communist Party Government will thank and remember you forever.” Julie Keith sent the letter to the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

The letter attracted international media coverage. Its author, Mr. Zhang, 47, had been detained as a supporter of Falun Gong, the banned spiritual movement which originated in China around 20 years ago, and sent to the Masanjia camp where he secretly wrote 20 letters over the course of two years.

In part instigated by this case, a public debate has begun in China regarding the practice of “re-education through labour”. Former labour camp inmates are detailing their experiences, ranging from unlawful arrests and incarceration without trial, to actual torture at the hands of guards in labour camps. They describe frequent beatings, days of sleep deprivation, months of solitary confinement and prisoners chained up in painful positions for weeks on end, as well as the deaths of fellow inmates, either from suicide or from an illness that went untreated by prison officials.

Shedding light on the atrocities committed in labour camps such as Masanjia is not without danger, as demonstrated by the disappearance of Chinese photographer and journalist Du Bin who has worked vigorously to uncover torture and other violations of human rights within China’s re-educational labour camps. According to Amnesty International, he was detained last month and questioned about his work, which could have been regarded as the crime of “causing a disturbance”. He was, however, released.

In China, there are about 350 re-education camps, first introduced during Mao Zedong’s 1957 “anti-rightist movement” campaign. The camps house three kinds of prisoners: delinquents (drug-addicts and prostitutes); members of Falun Gong and those who petition the xinfang system – a system that allows people to raise complaints about injustices committed – “too much”. The Masanjia labour camp opened in the late 1950s and is thought to hold thousands of men and women, often detained without charge or trial, sometimes for up to four years.

The anti-Chinese website Democratic Underground reports that from July 1999 to February 2004, at least 99 Falun Gong practitioners were murdered there, simply because of their belief in the universal principle of “Truthfulness-Compassion-Tolerance”, an ideology which Xinhua, the official news organisation of the Communist Party, declared was “opposed to the Communist Party of China and the central government, preaches idealism, theism and feudal superstition.”

The “re-education through labour” system is lucrative for the authorities: inmate labour is a huge source of income, and prison employees often demand bribes for early release or better treatment of inmates. In times of labour shortages, the camps simply “buy” small-time offenders from other cities for around $130 for six months of labour. Zhang Ling, 25 tells how she was arrested last May during a crackdown, only to be sold to Masanjia. Her brother paid for her release 10 months ahead of her time.

As Corinna-Barbara Francis, China researcher at Amnesty International says, “Given the serious money being made in these places, the economic incentive to keep the system going is really powerful”.

Numerous labour camps can be found in Tibet. Reports of torture of Tibetan prisoners in Drapchi Prison and other labour camps such as Sangyip are frequent and well-documented. According to a report written by The Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions from Tibet Justice Centre, re-education through labour is used often for the detention of political dissidents in both China and Tibet.

Find out more about Du Bin’s film and the Masanjia Camp by following this link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTUnvsl3gCI

Print

Print Email

Email