Bloomberg News

September 22, 2018, 2:30 AM GMT+5:30

The Potala Palace in Lhasa, China’s Tibet Autonomous Region. Photographer: Johannes Eisele/AFP via Getty Images

For three centuries, a succession of Tibetan spiritual and political leaders known as Dalai Lama ruled from a crimson-and-white castle overlooking the city of Lhasa.

The Potala Palace — as it’s known — was the start of a rare tour of Tibet last month. The Chinese foreign ministry and local government hosted international journalists on a trip to the mountainous region, and I was one of them.

While the Potala Palace still dominates Lhasa’s skyline, the current Dalai Lama hasn’t lived there since 1959, when the twenty-something fled to India as the People’s Liberation Army quashed a revolt against Chinese rule. In the six decades since, the question of his return has been a persistent source of tension between China and the West.

The Chinese government says the Dalai Lama can return only if he gives up any pretensions for an independent Tibet. The Dalai Lama and his supporters say they don’t seek independence but instead greater autonomy within China’s system, including an elected legislature and independent judicial system. Beijing rejects that claim as insincere.

But with the spiritual leader now 83, his return has also become a question of succession. In a move that could rile China’s ties with Western democracies, Beijing has begun laying out the case for why it should appoint the Dalai Lama’s successor instead of his exiled supporters in northern India.

It was a topic that came up frequently on our government-organized trip, which has long been the sole way foreign journalists could travel to Tibet — the only part of China where written permission is required to visit. Such trips have also become rarer after a spate of self immolations earlier this decade prompted tightened security. Beijing blames the Dalai Lama, who it says has fomented the unrest, while his followers and human-rights activists say the cause is government oppression.

Tibet stands out as the only Chinese area where ethnic Han Chinese are a small minority. Of the 3.2 million who live in the mountainous region, more than 90 percent are ethnic Tibetan. China’s total population of 1.4 billion, by contrast, is more than 90 percent Han.

Shopping area in Lhasa.Photographer: John Liu/Bloomberg

In April, the U.S. State Department blasted China for “severe” repression in Tibet, including arbitrary detention, censorship and travel restrictions. It counted five incidences of self-immolation in 2017 — a drop-off from 83 in 2012 — and noted the arrest of Tibetans who speak with foreigners, particularly journalists.

The Potala Palace was the first of many stops in our packed itinerary, which also included visits to businesses, holy sites, an orphanage, the home of a herdsman, a school teaching traditional Thangka painting and interviews with various local authorities. At each stop, we were able to ask whatever we wanted as officials looked on.

At the Dalai Lama’s former residence, we saw pilgrims leaving offerings of money in the room where he once received guests. On the wall was a portrait of the 13th Dalai Lama, predecessor of the current reincarnation.

While our questions about the Dalai Lama at the palace and other stops were mostly met with polite reticence, the reverence he still commands was noticeable. Several local officials said he’s still held in esteem by many as a spiritual leader.

The Potala Palace also holds the tombs of eight past Dalai Lama. The title passes from generation to generation through a process that selects successors in their childhood as reincarnations. Supporters of the current Dalai Lama fear that upon his death, there will be two claimants to the position: one selected by them and another by the Chinese government.

Gyaltsen Norbu, China’s official Tibetan spiritual leader, the Panchen Lama.Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

A similar power struggle played out with the Panchen Lama, the second-most prominent figure in Tibetan Buddhism. After the death of the 10th Panchen Lama in 1989, both the Chinese government and the Dalai Lama identified reincarnations. The man selected by Beijing is now a senior adviser to the nation’s parliament. The Dalai Lama’s choice hasn’t been seen in two decades, and his followers say he was abducted at the age of six.

His disappearance has become a political issue. In April, the U.S. State Department issued a statement marking his birthday and called on Chinese authorities to release him immediately, provoking a furious response from Beijing.

The Central Tibetan Administration, which represents the Dalai Lama’s followers in northern India, says the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama should be in the hands of Tibetan Buddhist leaders. “The Chinese government should not interfere in the religious practices of Tibetan Buddhism,” said spokesman Sonam Dagpo.

When we discussed this with officials our trip, they argued that there’s precedent for Beijing to be involved. The current Dalai Lama, they say, ascended to the position in 1939 after being approved by Chiang Kai-Shek, who was president of the Republic of China before the Communist Party took power in 1949.

They also said the Communist Party has done just fine running Tibet. Some data points they reeled off: The economy has seen double-digit growth in each of the last 25 years; average life expectancy doubled to 68.2 in 2017 from 32.7 years in 1959; and literacy is now more than 99 percent, up from about 2 percent in 1951.

Central government statistics show that Tibet’s average disposable income was about $5,300 last year. That’s less than the national average, but higher than several other regions including Gansu and Heilongjiang in the north.

Signs of growth were evident on the ground. In Lhasa, where we spent most of our time, scores of buildings were under construction. Traffic is bad from morning until as late as 9 p.m. A BMW dealership had opened, as has an enormous JD.com Inc. warehouse.

Tibet’s problems under the Dalai Lama’s rule went beyond economics, said Luobu Dunzhu, the most-senior official we met on our trip. The 57-year-old executive vice chairman of Tibet’s regional government told our group that his parents were slaves in the feudal system the Dalai Lama headed, and had no hope for an education or better lives. Tibetans don’t want to go back, he said.

“The Dalai Lama knew about all of these problems and didn’t do anything to solve them,” Luobu Dunzhu said. “It was the Communist Party that changed Tibet and that’s why the people support the party.”

The Dalai Lama’s followers in India say that economic growth has mainly benefited ethnic Han Chinese, and deny they want to reinstate the old feudal system.

What they want, spokesman Dagpo said, is for Tibetans to be able to worship and travel freely, to carry photos of the Dalai Lama and to send their children to monasteries. A key problem with Chinese rules is that any advocacy for Tibetan rights is seen as a form of intolerable separatism, he said.

While we saw no signs of unrest during our trip, the concern about separatism was clear. Travelers flying into Lhasa have their identifications checked before they can exit the airport. Roads entering the capital are manned by police checkpoints. Foreign tourists need permission to visit, one official said, to prevent “bad guys” from sneaking in.

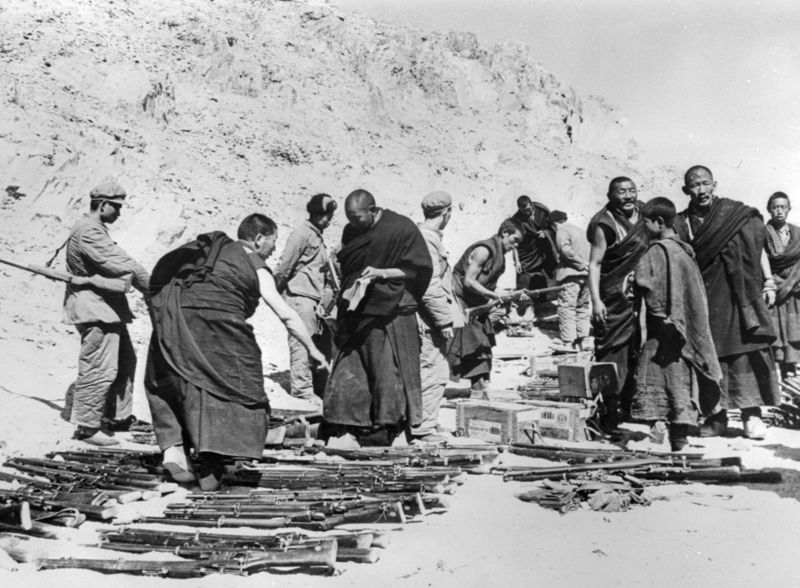

That concern was also discernible when we visited the Sera Monastery, which dates back to the 1400s and where monks died in fighting with Chinese troops during the 1959 uprising when the Dalai Lama fled Tibet.

Tibetan monks, surrounded by Chinese PLA soldiers, lay down arms in April 1959.Photographer: AFP via Getty Images

The monks there still practice many of its oldest traditions, including debate sessions in which participants whirl in circles and slap their hands together. But there’s also been change. In addition to Buddhist scriptures, its library also carries copies of President Xi Jinping’s book, “The Governance of China.”

Suo Lang Ci Ren, a member of the Sera monastery’s management committee, articulated a view we heard from several religious figures — one that Beijing may also like to hear from the next Dalai Lama.

“Loving your country and loving your religion,” he said, “are things a monk must do in parallel.”

— With assistance by John Liu, Iain Marlow, and Xiaoqing Pi

Print

Print Email

Email