Brendan Ozawa-de Silva

Photo: Emory University Website

In efforts to cultivate frameworks for emotional intelligence in modern education systems, researchers, educators and scientists have committed to bringing evidence-based social emotional learning to schools worldwide. In this article, we explore the foundations of SEE Learning (Social, Emotional and Ethical Learning), the first social emotional learning curriculum developed on the basis of “secular ethics” and its shape within the social emotional learning movement. To do this, Contact magazine reached out to the Associate Director for SEE Learning at Emory University’s Centre for Contemplative Science and Compassion Based Ethics, Brendan Ozawa-de Silva.

Onwunli:

Brendan, why don’t you tell us a little about yourself and how you got involved with SEE Learning?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“Sure, I’m the Associate Director for SEE learning at Emory University’s centre for Contemplative Science and Compassion Based Ethics. Before that, my background was a professor of psychology. I also did a PhD in Buddhist studies. My background is in meditation research, and how to bring contemplative theory and contemplative practices, particularly from the Indian and Tibetan traditions, into contemporary society, particularly through education into what the Dalai Lama calls secular ethics. I was invited to help develop the SEE Learning program by our director, Dr Lobsang Tenzin Negi, who is a Geshe and former monk in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, as well as a professor at Emory University.

“If we don’t have a way of bringing secular ethics into education and into different parts of society, then we have no way of talking about our common basic human values.

Onwunli:

Could you tell me in your own words, what SEE learning’s purpose? Who is it for? Who is it meant to benefit?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“SEE Learning is an effort to bring secular ethics into education. Secular ethics, as His Holiness the Dalai Lama defines it, is basic human values. So, values like compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, generosity and empathy. Values that we have as human beings, regardless of our culture, regardless of our religious tradition, regardless of our lack of religious tradition. These values are shared by all the world’s religious traditions, but they’re also shared by people of no religion. It isn’t appropriate in every case to bring ethical values into society and into education on the basis of religion, but we can bring ethical values in through a universal, secular approach.

We see the increasing pluralisation of the world, increasing religious diversity, and an increasing number of people who are non-religious. Over one billion people in the world say they’re not religious. If we don’t have a way of bringing secular ethics into education and into different parts of society, then we have no way of talking about our common basic human values. Then the problem is, since we have no language for discussing values, we cannot really engage in the common cultivation of those values. Then what’s left could be just materialism and a focus on material wellbeing alone.

Our target audience is educators and students around the world. It’s a free programme, we are trying to translate it into as many languages as possible. We have currently 18 languages that it’s being translated into. Our mandate from His Holiness the Dalai Lama was to help create a global movement, to bring secular ethics into education. It’s really a worldwide perspective that we’re trying to take.”

Onwunli:

During the programme’s formation, what would you say were SEE Learning’s most difficult hurdles?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“I think the most difficult hurdle has been the scale of the programme. Most people don’t try to create a programme that is for worldwide adoption. But His Holiness the Dalai Lama encouraged us to, to think big and think about the entire world in our programme. The implementation of such a programme with integrity, fidelity and quality is a major challenge.

Education systems are not the easiest systems to transform. Every country has a different education system, there isn’t a single education system. So the logistical challenges and the challenges of high quality implementation might be the biggest hurdle that we have.

The research tells us that it’s not evidence-based programming that brings about change in schools; it’s evidence-based programming that is implemented at a high level of quality that brings about change. However, we’re very fortunate to have incredible affiliates, collaborating individuals and organisations around the world helping us to make this a reality. We were very fortunate to have the support and patronage of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in promoting the programme. Despite the scope of that challenge, I think we’ve made some really great progress.”

Onwunli:

Could you give us an example of one of your favourite or more impactful lessons unique to SEE Learning?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“We have a lesson that’s introduced very early in the curriculum called “compassion as an inner quality”. We tried to go a bit deeper to really encourage the students to explore what compassion and kindness really are. Part of that is understanding that compassion and kindness are not just the actions we do, but the motivations and the feelings behind those actions. The lesson gives different little stories and scenarios, and then asks the students, “Who was actually being kinder?”, “Who was actually being compassionate in this story?”. Sometimes the outer actions appear kind, but the inner motivation might be different. For example, in one of the stories, a new student joins the school and the student had prior experience playing a sport like soccer or football. The team captain says to a few of his team members, “You know, let’s go be nice to this new kid, to recruit this kid to join our team, because their joining our team would really help us. So, everybody be friendly, and tell them all what a nice, great team we have and get them to join.” Then we have a discussion with the kids in the classroom and ask, “Is that kindness? Is that compassion?” The point is not for them to have a yes or no answer. The point is, for them to have a conversation around what that means.”

“Whether it’s generosity, gratitude, forgiveness, it’s all done through this exploratory way with the students. It’s like a Socratic method, where they engage in dialogue, and they come to their own conclusions.

“Later in the curriculum, we have a story in which a younger girl, a student, is climbing trees. An older student sees this girl trying to climb the trees and the teacher says to the older girl, “Could you tell her that she can’t climb the trees? We have a school policy where you can’t climb the trees”. The older girl says, “No, I don’t want to tell her that because she’ll think I’m being mean to her, because she likes climbing trees”. The teacher says, “The reason we have this rule is because when kids climb the trees, there’s a chance they could fall and she’s very small. If she falls, she could really hurt herself. So, you need to tell her that she can’t climb the trees.” The students then discuss what the older student might do and feel, what the younger student might do and feel, and how this might be understood. They explore the idea that sometimes you may have to say no to someone to be kind to them, to be compassionate. You’re not being mean by saying no, you’re motivated by kindness. The point is for them to discuss, reflect and explore for themselves.

Kids, even from quite a young age, 5, 6, 7-year old’s, they can understand the complexity of these scenarios. What it’s doing is introducing them to the idea that sometimes what looks like a kind action is a little more complex. And sometimes what looks like an unkind action, like telling someone, “No you can’t do this, you have to stop”, could actually be a kind action. So, that idea of exploring more about what kindness and compassion is and having discussions about it, is really key to our programme. We explore everything that way, whether it’s generosity, gratitude, forgiveness, it’s all done through this exploratory way with the students. It’s like a Socratic method, where they engage in dialogue, and they come to their own conclusions, except it’s not just through talking but through engaging activities too. The constructivist pedagogy in SEE Learning means we’re not telling them how they have to behave or how they should behave, we are introducing them to some of the complexity of these situations and emotions, and in almost every case, their understanding of these basic human values increases through this constructivist process.”

“Social emotional learning had already talked about social skills, but it didn’t emphasise ethics and compassion.”

Onwunli:

I understood that Social Emotional Learning (SEL) was initially a movement just within the scientific community before SEE Learning was created. SEE Learning is now being called SEL 2.0. How did we get from SEL 1.0 to SEL 2.0?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“The social emotional learning movement was started over 20 years ago. Two of our key advisors, Dr Daniel Goleman, and Linda Lantieri, were co-founders of the social emotional learning movement and the current organisation that supports it, called CASEL, the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning. We also have several other advisors that are very intimately connected with CASEL as well, including Mark Greenberg, Kimberly Schonert-Reichl and others. That movement is still alive and well, it hasn’t gone anywhere. In fact, it keeps growing in the US and around the world.

Along the way, as we’re always learning new things, the founders of CASEL have been calling for the further development and expansion of social emotional learning. One of the things that Linda Lantieri has been calling for is the incorporation of mindfulness and contemplative practice into social emotional learning. Similarly, Daniel Goleman has been calling for additional components. He laid this out in a book called The Triple Focus that he wrote with Peter Senge. He names three. The first is an “inner focus”: awareness of the self, contemplative practice, attention-based practices. Not just attention to external things, but attention to what’s happening inside the mind. Attention to emotions, beliefs and attitudes. The second is an “other focus,” which is the cultivation of compassion and care, how we relate to others. Social emotional learning had already talked about social skills, but it didn’t emphasise compassion very centrally. Compassion is believed by many, including Dr Goleman, Linda Lantieri, the Dalai Lama and many, many others, as one of the most beneficial ways we can improve our way of relating with others. The centralising of compassion in SEL also gives us the opportunity to talk about ethics in a secular way, since we can introduce the idea of a compassion-based ethics, namely one based on our common humanity and interdependence.”

“SEE Learning sought out to introduce secular ethics to education on the basis of also adding these other core elements, that the leaders of the SEL movement were saying would lead to the further evolution of SEL”

“Dr Goleman and Dr Senge’s book also calls for an “outer focus,” which means systems thinking. Prior to SEE Learning, no social emotional learning programme had combined social emotional learning with systems thinking. Only a few of them have combined it with practices like mindfulness and other contemplative practices. A few of them have focused on compassion, but not all. SEE Learning sought to introduce secular ethics to education on the basis of also adding these other core elements, that the leaders of the SEL movement were saying would lead to the further evolution of SEL; systems thinking, compassion, ethics and contemplative practice or reflective practices. In addition, we added something that is also emerging in the field, which is trauma-informed practice, meaning a focus on the nervous system and the body. Because understanding the brain and the nervous system, and how it responds to stress and wellbeing, is extremely important and we’ve had huge scientific advances in that area in recent years. Understanding that and introducing practices that tap into that knowledge is really helping educators and students. Bringing all these additional components to SEL, and by having this focus on ethics and basic human values, led to Dr Goleman calling SEE Learning “SEL 2.0, showing the future direction for SEL programming.” So, it’s not that SEE Learning is in any way replacing SEL. This just is one direction in which these programmes can fruitfully evolve.”

Onwunli:

Would you mind explaining systems thinking in this context? That might mean different things for people of different disciplines.

Ozawa-de Silva:

“Systems thinking is a way of approaching situations and approaching phenomena through the lens of interdependence. When we try to understand something, we can understand it in one of two ways: we can understand it in a reductive way, where we basically try to look at the thing by itself, independent of context, and understand it. Or we can look at it through the lens of relationships. How does it relate to other things? What makes up this thing, or this event?

One example is, we choose a simple thing like a sweater. We ask, what goes into making up the sweater? We look at the sweater relationally, we look at the sweater through the lens of interdependence. Does the sweater just come from nowhere? Kids know that’s not true. If it’s a woollen sweater, it comes from sheep. Well, where are the sheep? They’re on a farm, so you need farmers. Do you need trucks? Do you need roads etc? Even little kids 5, 6, 7 years old, know that things come from other things, so they can explore that process. When they explore the process of interdependence, that’s an exercise in systems thinking. We start to realise that our food, our water, our shelter and our clothing all come from networks of many other people. What that does is it helps us to understand how interdependent we are, because then we can feel grateful to the people who help sustain our life and everything that we need to live. We can also understand that their actions impact us, and our actions impact them. So that introduces an ethical component that we wouldn’t necessarily be as aware of if we just looked at everything reductively, if we looked at everything independently.”

“Understanding feedback loops is a common component of systems thinking. Even small kids can really understand these feedback loops.”

“Another example of systems thinking is the feedback loop. My interaction with you could create a constructive feedback loop, or possibly a destructive feedback loop. We use an example of a kid sharing something. I share my lunch with you because you forgot your lunch. Then the next day, if I forget my lunch, are you going to be more likely to share your lunch with me because I shared it with you? If you share your lunch with me, then this creates a relationship between us. That can create a positive loop, where we start helping each other more and we become closer. But what if I shared my lunch with you one day and the next day, I forgot my lunch, and you say, “No, I’m not going to share my lunch with you” and instead you’re just mean to me. That meanness could start a negative loop. Understanding feedback loops is a common component of systems thinking. Even small kids can really understand these feedback loops. Systems thinking can become extremely complex, we can talk about extremely complex mathematical modelling of feedback loops, it’s a whole field of science and mathematics. We’re not introducing those complex equations to 7-year olds, but the basic concepts are actually exactly the same. About interdependence, about feedback loops, about complexity. This is a good example of how we’re still doing system thinking; we’re just doing it in a way that’s more practical and accessible to children. Then we can build up through the curriculum to extremely complex, sophisticated ways of looking at the world.

Onwunli:

How many institutions are using SEE Learning as a core part of their curriculum? Are there regions of the world that remain relatively untouched?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“Currently, we have had about 15,000 educators who have received training in SEE Learning directly from us, that we that we know of, either through our online platform, virtual trainings, or through in-person workshops that we’ve done. The actual number of educators reached would be much higher, because we also have efforts underway in 35 countries to prepare facilitators and educators to deliver SEE Learning through our international affiliates. We also have 280 facilitators in training; these are sometimes called “teacher trainers”. These certified SEE Learning facilitators can hold workshops for educators and will thereby be able to reach tens of thousands more educators. What we’re concentrating on right now is building up the infrastructure for the programme, through having quality facilitator training, quality educator training and quality implementation support. That will allow us to scale with quality, integrity and fidelity. We and our international affiliates hope to reach several million children in the next three to five years. For that to be quality implementation, we need to build up the infrastructure.

Our scale of implementation also varies according to where we are in the world. Some countries like Ukraine are engaged in efforts to roll out SEE Learning nationally. Mongolia has plans to do that, as well as a few other countries. Some organisations are supporting regional rollout, within a state or region of the country. In Tuluá Colombia, we have the city government, the mayor and the Secretary of Education at the city level, rolling it out to all schools in the entire city. Thanks to our affiliates there at the Levapan Foundation, every educator in that city, at every school in that city will be exposed to SEE Learning and will be receiving some training in SEE Learning. We have school districts in the US, like the City Schools of Decatur and Atlanta Public Schools, also rolling out SEE Learning on a wide scale; just these two districts are allowing SEE Learning to reach more than 10,000 students in the greater Atlanta area. Then we have individual schools where there’s no city-wide or region-wide implementation, but the school has signed on to implement SEE Learning across the board. There are many different levels of implementation, and we’re only of course a year and a half post launch. There are many seeds that have been planted. We’ll probably know better in a few years where we stand in terms of overall reach.”

Onwunli:

Would you say that there are existing political or cultural barriers to widening or spreading the use of this curriculum?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“I think one of the biggest obstacles would be people who think that ethics cannot be separated from religion. Some people think that teaching about ethics or discussing basic human values automatically means that you’re teaching a set view of morality, and therefore that you’re teaching religion. I think this is not true of our approach. First of all, we are exploring basic human values; we’re not teaching basic human values. We believe that the core components of these basic human values are actually innate, they have a biological basis. This is why we don’t find any human culture or any human religion where integrity is not valued, wisdom is not valued, compassion is not valued, gratitude and generosity are not valued, self-discipline is not valued. That would be a pretty scary society, if we were to find such a place. We don’t find that. What we find is that there’s a lot of commonality around basic human values. Psychology, neuroscience and other disciplines are showing us that even mammals and birds have elements of these pro-social emotions and pro-social behaviours. Some of our basic human values are probably rooted in our evolutionary history. Which is why when we see mammals, for example cats, we see that when a cat loses her kittens, she goes searching for her kittens. Why is she searching for her kittens? She can search for days. We see elephants, when one of their young gets trapped, in a swamp for example, all the elephants come and try to bring that baby elephant out of the swamp. So what’s happening there?”

“There is a way of approaching ethics that is common to all religions and just common to humanity. We cannot say that all ethics and all morality have to be dependent on religion. It’s important to say our programme is not in any way opposed to religion”

“These are actually the same behaviours we see in humans. These are behaviours that anybody in any culture and any religion can understand. You don’t need to be explained or told what’s happening here. As human beings, we all rely on kindness and compassion in order to survive. None of us when we’re born can survive without the kindness of others. We’re not self-sufficient. It’s built into our biology and our psychology to appreciate kindness, because without kindness, our species does not survive and no mammalian or bird species can survive without kindness, because we all depend on maternal care. This is why His Holiness the Dalai Lama says, “Love and compassion are not luxuries, they are the very basis of our survival”. This perspective is emerging in science, in philosophy, even in economics and other disciplines, we’re realising that we have these basic human values. Religion can add many wonderful things on top of them, but there is a way of approaching ethics that is common to all religions and just common to humanity. We cannot say that all ethics and all morality have to be dependent on religion. It’s important to say our program is not in any way opposed to religion and when we use the word “secular ethics”, we do not mean the word “secular” as opposed to religion or anti religion, we mean, universal and non-sectarian.

We emphasise constructivist pedagogy, meaning that the student constructs their knowledge, co-creates, co-explores that knowledge, facilitated by the teacher, and in communication with their fellow students and the teacher. It’s not a transmission model of knowledge. It’s not that we adults have figured out the best way to be ethical, the best way to be moral, and then we teach the children what to do, and we tell them what to do. Constructivism is a very different approach, it’s closer to the Socratic model and it’s based around dialogue, investigation and exploration. This is the way a lot of science education is done nowadays. If you want to train these students to be scientists, to be explorers, to investigate phenomena for themselves, then you’re actually teaching them an approach to science, you’re not just telling them facts about the world. Because the scientific facts about the world might change, 20 years from now, 30 years from now. What’s much more important is teaching the method of investigation. What excites me about this approach is that it’s very possible that future generations could have more sophisticated ways of understanding ethics and emotions than we do now. And we’re preparing them for that.”

“We want this to be an evidence-based programme and an evidence-based science-informed approach to secular ethics”

Onwunli:

Are there any schools that you would say are exemplary or model examples at the moment? Or is it too early to say?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“We do have several model schools and what those schools have in common is they have very strong administrative support, as well as strong support from the faculty. Administrative support is extremely important to having sustainable implementation. The corollary to that is also the ability to partner long term with us. The schools where things are working the best is where the administrators have made a multi-year commitment. We’re really able to foster SEE learning in that environment. Some of these schools have even offered themselves to serve as lab spaces, because we have a very strong research component to our programme. We want this to be an evidence-based programme and an evidence-based science-informed approach to secular ethics. These schools have really been incredible resources to us and have been fantastic. It’s been wonderful to see the transformation of these schools over the years.”

Onwunli:

What kind of outreach is conducted? Do institutions come to you, or do you go to them? How is SEE Learning spread essentially?

Ozawa-de Silva:

“Up until now, it’s largely been spread by word of mouth. And it’s largely been spread by people hearing about this programme, and then coming to us, including the significant number of people who have heard about this programme from His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Because we are a free programme, and are actively looking for affiliates, we welcome all connections. We would want all your readers to know that we’re always open to people reaching out to us to help bring SEE Learning to their communities. It’s been gratifying to see the incredible amount of interest in the programme around the world. Although we are going to be looking at strategically engaging certain regions of the world where we haven’t yet had contact.”

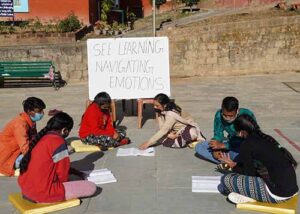

Some photos of their programs across the world :

Interviewed by Okechukwu Onwunli on November 10, 2020

To read previously published news and articles on Secular Ethics on Contact, visit here

Print

Print Email

Email