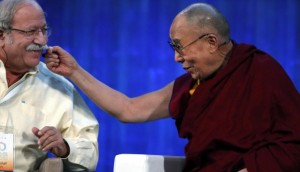

The Dalai Lama and Harvard University’s Professor Marshall Ganz during a panel discussion in the United States in October

Photos: AP; AFP; Corbis; EPA

He’s not your average 79-year-old. The Dalai Lama looks strong and moves with purpose. He’s a powerful, towering presence. Last week, the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet delivered Buddhist teachings day after day to thousands of people at his temple in Dharamsala, in northern India, in sessions lasting four hours at a time.

He has predicted that he won’t die until he’s 113 – that’s another 34 years – and so it seemed rather premature, back in September, when he told German media that he was thinking of making himself the last of the line. There might be no 15th Dalai Lama.

“We had a Dalai Lama for almost five centuries,” he told the Welt am Sonntag newspaper. “The 14th Dalai Lama now is very popular. Let us then finish with a popular Dalai Lama.”

His comments sparked headlines around the world, an outcry of disbelief from Tibetans and fury from Beijing. So why did he make such a statement, and if he was serious, what would that mean for Tibetans inside and outside Tibet?

While some scholars believe he was speaking in earnest and that it is a strategy for dealing with China, the end of the Dalai Lama institution might not cause as many waves as some fear. It is actually not unheard of for lineages of incarnate lamas to be stopped and, sometimes, restarted – the Shamarpa line, for example, was banned by the Tibetan government at the end of the 18th century and then brought back in the 1960s.

But the current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is such a revered figure among Tibetan Buddhists that many Tibetans in Dharamsala dismissed the news story outright. He was misquoted, said some. Others claimed he was just being mischievous – after all, the Dalai Lama is known to enjoy a joke from time to time.

“I don’t think he was being serious,” says 25-year-old Kunga Jampa, a Tibetan teacher in Dharamsala. “He was just joking … At school we were taught that His Holiness is our father and our mother, ahead of our real father and mother. Without him we are nothing.”

A monk in his early 30s who came to India last year from a Tibetan area of Yunnan province is also having none of it. Shaking his head, he says: “The Dalai Lama’s work is not over yet. Until all sentient beings are delivered from suffering he will keep coming back.” The monk does not want to give his name because he is planning to return to China next year.

“This cannot possibly happen,” says a Tibetan man from Sichuan province who has been living in exile in India for seven years and also does not want to give his name. “The Dalai Lama is the representative of everything about Tibet – its culture, its people, its religion. No, no. I don’t believe it. I don’t believe that he will not be reincarnated.”

In Beijing, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said the Dalai Lama had no right to dictate.

“The title of Dalai Lama is conferred by the central government, which has hundreds of years of history,” Hua told reporters at a regular press briefing. The Dalai Lama, “has ulterior motives, and is seeking to distort and negate history, which is damaging to the normal order of Tibetan Buddhism”.

So who does have the right to decide on whether there is a 15th Dalai Lama or not?

The Dalai Lama’s office, known as the Gaden Phodrang and based in Dharamsala, has this 2011 statement, attributed to the Dalai Lama, on its website: “When I am about 90 I will consult the high Lamas of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions, the Tibetan public, and other concerned people who follow Tibetan Buddhism, and re-evaluate whether the institution of the Dalai Lama should continue or not. On that basis we will take a decision.”

The decision that would be most popular with the Tibetan people, says the man from Sichuan, would be for the line to go on.

“More than 99 per cent of Tibetans want to see the Dalai Lama line continue, and they are the ones who have the right to decide,” he says.

Dr Martin Mills, a Tibetologist at the University of Aberdeen, in Scotland, explains that, historically, it is the estate or office of the Dalai Lama that has the authority to make such decisions, although down the centuries it has not been unusual for political tensions to crop up when naming the next in line.

Tibetans gather at the Potala Palace, in Lhasa, Tibet, in March 1959, in an unsuccessful armed uprising against Chinese rule.

Tibetans gather at the Potala Palace, in Lhasa, Tibet, in March 1959, in an unsuccessful armed uprising against Chinese rule.

“The tradition of the ‘incarnate lama’ [or tulku] emerged in Tibet in the 12th century”, with an older Tibetan Buddhist school, the Kagyupa, explains Mills. These lamas held power and property that were looked after by an estate, called a labrang. “Ultimately, it is the labrang of an incarnate lama that has the right to name that successor,” he says. The successor was chosen through various religious and mystical procedures.

The Gelukpa tradition borrowed the idea of incarnate lamas from the Kagyupa school and the Dalai Lama lineage began in the 15th century. By the 17th century, the Dalai Lama and his labrang, the Gaden Phodrang, were in political control of Tibet. Sponsors of the Dalai Lama – such as kings, Mongolian chiefs and the Chinese emperor – frequently tried to influence the choosing of a successor.

“In most cases, Lhasa tended to ignore this authority or hold it at a diplomatic distance,” says Mills.

Gray Tuttle, associate professor of modern Tibetan studies at Columbia University, in New York, views the question from a more religious angle.

“From the perspective of Tibetan cultural tradition, the only person who has the authority to decide this would be the Dalai Lama himself,” says Tuttle. “This is because the whole theory of reincarnation of special lineages of lamas is based on the enlightened state of the lama him- (or more rarely, her-) self. He is uniquely qualified to decide on his own reincarnation status for the future. And if he were to decide not to reincarnate, that would be understood to be totally within his rights, and solely his prerogative, to decide.”

Beijing, he adds, “most certainly does not have any right to decide this”.

Both Tibet and religion are sensitive topics in the mainland because they are seen as challenges to the one-party state. Beijing makes the major decisions in Tibet and oversees all permitted religions in the country, through the State Administration for Religious Affairs. For example, the Chinese Catholic Church is not permitted to recognise the authority of the Vatican.

The Dalai Lama is greeted by well-wishers after delivering a lecture near

The Dalai Lama is greeted by well-wishers after delivering a lecture near

Dharamsala, India, last month.

“The 14th Dalai Lama himself has no right to decide his incarnation,” says Dr Zhang Yun, a director of the Institute of History at the China Tibetology Research Centre in Beijing. “He is only one of many living Buddhas. Even for his own Dalai Lama system, he’s only the 14th one, so he can’t decide the fate of this system on behalf of all his predecessors.”

Zhang says that the 15th Dalai Lama must be approved by the central government, but adds “if Tibetan Buddhists and monks believe that the Living Buddha reincarnation system, especially the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, has no reason to exist any more, that would be another case”.

Any historical claim by Beijing over his institution ended when the Dalai Lama escaped into exile, argues Mills. The Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959, along with tens of thousands of Tibetan refugees.

“In fleeing into exile … the Dalai Lama renounced any legal claim to his lands in Tibet,” says Mills. “It’s unclear what the nature of the Chinese claim is, unless they’re simply saying they have authority over all Tibetan things, cultural, religious or otherwise, wherever they may be.”

He may have lost all power over Tibet in 1959 but, in exile, the Dalai Lama adopted the role of spiritual and, until 2011, political leader of the Tibetan diaspora. Three years ago, he handed the political reins over to a former Harvard University academic, Lobsang Sangay, the elected prime minister of the Tibetan government in exile, the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA).

For more than 50 years, the Dalai Lama has been the galvanising force behind the Tibetan cause. That includes a call for Tibetan independence, or, as the Dalai Lama in his later years has come to advocate, autonomy in a Tibet under Beijing’s rule – what he calls a “middle-way approach”. So without a Dalai Lama, what would happen to the cause?

Tibetans, scholars and campaign groups agree that, in the long run, the cause would continue. The Dalai Lama is a figurehead for the movement but he’s not its raison d’etre.

“The Dalai Lama is clearly, at the moment, the greatest asset the Tibetan movement has: his public profile and also, obviously, his role, his personality, his status as an advocate for peace,” says Alistair Currie, media officer of British-based campaign group Free Tibet. “I think it would be naive to say his passing would not pose a challenge to the Tibetan movement.”

The Dalai Lama gives a talk in Hamburg, Germany, in August.

The Dalai Lama gives a talk in Hamburg, Germany, in August.

However, “a lifetime of occupation and undimmed resistance won’t stop when the Dalai Lama dies”, he says. “His passing will change what they do but the resistance [to Chinese rule] will continue.”

Kunga Jampa, the young Tibetan teacher, agrees: “The issue will still be there whether the Dalai Lama is here or not … the Dalai Lama has told us Tibetans to be more independent, to not always rely on him. When he passes away, we have to start to do things by ourselves.”

Some Tibetans have shown their frustration with Chinese rule through protests – the latest major one being in 2008 – and others through self-immolation; there have been 130 since 2009, according to the CTA.

“In the long run, the death of the Dalai Lama and even a discontinuation of the institution of the Dalai Lama might not change that much inside Tibet,” says French Tibetologist Thierry Dodin, who is associated with the University of Bonn, in Germany. “As much as the Chinese authorities seem to believe that the Tibet issue is, in fact, a Dalai Lama issue, and as much as more radical Tibetans and Tibet supporters believe it is linked to the question of whether Tibet was, is or should be independent, all evidence at hand indicates that the Tibet issue is, in fact, all about the frustrations of Tibetans inside Tibet living an alienated life under an essentially colonial regime.

“The Tibet issue will continue with or without the Dalai Lama.”

Whatever the 14th incarnation might decide, Beijing may insist on appointing a 15th Dalai Lama anyway.

“China would certainly choose its own Dalai Lama, so there will be a 15th Dalai Lama of some sort,” says Elliot Sperling, an associate professor at Indiana University, in the United States, who is researching Tibetan history and Sino-Tibetan relations. “But it is likely that a Chinese-chosen Dalai Lama would be either outrightly rejected or ignored by the majority of Tibetans.”

Tibetan Buddhist monks attend a teaching session by the Dalai Lama at the Sera Monastery, in Karnataka, India.

In 1995, the Dalai Lama named Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the 11th Panchen Lama (another top lama in the Gelukpa school). The six-year-old boy “disappeared” soon after and Beijing appointed its own choice. Gedhun Choekyi Nyima has not been seen since. Few Tibetans have embraced China’s choice, as any visit to a monastery in Tibet will demonstrate. The portrait of China’s Panchen Lama is rarely displayed, whereas the portrait of the previous incarnation, the 10th Panchen Lama, is often on show.

Over the past decade, a lot of thought has gone into potential leaders in the absence of the Dalai Lama, because even if there was a 15th, there would be a gap of about 15 to 20 years before the new incarnation was old enough to take on his role – spiritual or otherwise. A few years ago, the Western press were touting the Karmapa, the head of the Kagyupa school of Tibetan Buddhism, as a winning candidate. His good looks, his scholarship and the fact that as a teenager he had also escaped from China were promising credentials. However, the buzz over Ogyen Trinley Dorje has died down somewhat in recent years.

But Dodin believes the Karmapa is “the only major Tibetan religious leader who has known both life inside [Tibet] under China and life in exile. That is a major asset. He is also energetic and intelligent. With enough maturity he would certainly be an excellent leader.” However, he also believes there might be no need for a new leader or a leader that is a high lama.

Other galvanising figures, he says, will emerge, perhaps a charismatic ex-political prisoner. Dodin suggests we may yet see a Tibetan Nelson Mandela. He won’t name names, but says, “That figure is likely to be in Tibet rather than in the Tibetan exile community.”

In some ways, Tibet in exile already has another leader. Kunga Jampa says there is no reason for people not to get behind the prime minister: “Lobsang Sangay is certainly strong enough to carry on the cause.”

Tibetans inside Tibet know his name and his face, even though the government in exile is a sensitive topic. Last year, shops in Tongren, a Tibetan town in Qinghai province, were selling posters of the Dalai Lama posing with Lobsang Sangay and the Karmapa.

The Beijing-selected 11th Panchen Lama, Gyaincain Norbu (centre), who is not recognised by the Dalai Lama, attends the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in Beijing in March.

It is clear that the loss of the Dalai Lama line would cause a great deal of angst and political tension. And this brings us back to that quip to the German reporters in September. What was going through the Dalai Lama’s mind?

Dodin believes he is trying to solve the problem of having two Dalai Lamas. If the institution ends with him, then Beijing won’t be able to create the same charade it did with the Panchen Lama.

“I believe the current Dalai Lama is not concerned about a possible discontinuation of the institution of the Dalai Lama. What he is most concerned about is a continuation of the institution of the Dalai Lama under the control of China.”

It’s not the first time, adds Dodin, that he has voiced the possibility that he may be the last Dalai Lama. It “is part of a reflection in process”.

“I would guess that the Chinese state’s recent efforts at decreeing themselves as the sole legal authority that has the right to recognise reincarnations might be part of his decision,” says Tuttle. The political tussle over naming the next Dalai Lama might be so damaging to Tibetan Buddhism that it would be better to put an end to the line, he says.

Zhang, on the other hand, says, “The 14th Dalai Lama hyped the reincarnation question in order to control the reincarnation so that he can get to his political goal. It is not a religious question any more. It’s totally a political question.” As it clearly is for Beijing, too.

Meanwhile, in India, it’s back to work for the 14th Dalai Lama, who is very much alive and well. In the third week of December, he is due to travel to Karnataka, in the south of the country, for several days of public teaching. At these events, thousands of Tibetans, dressed in their finest, jostle with each other to catch a glimpse of their spiritual leader as he sweeps past them to his lectern. Those with babies and infants raise them onto their shoulders, hoping he will stop, notice them and squeeze their children’s cheeks.

Seeing their devotion, it is perhaps comforting to think we might have another 34 years before the issue of a successor must be decided.

Print

Print Email

Email