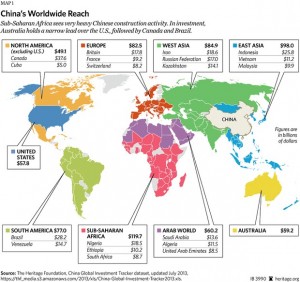

As the world’s second largest economy, China is fast becoming the world’s biggest international investor. The Heritage Foundation, the American think tank looking at public policies, has mapped the scale of China’s global investments at over $780 billion in over 93 countries across the globe.

Increasingly, countries are setting their sights on China to meet their investment needs. For some countries, China has proven it has deep pockets and the potential to invest in large-scale projects. For other countries, Chinese investment appeals as the agreements are more focused on economics and less on the country’s internal affairs. Unlike the European Union and America, China places minimal political conditions on co-operation, whereas investment agreements with the West demand assurance of good governance, the rule of law and protections for human rights. For example, China invested in Zimbabwe, Sudan and Myanmar at a time when the West boycotted or sanctioned the authoritarian regimes. Many emerging countries are also inspired by the success of China’s economic model and hope that in working with China they too can make big improvements in lifestyle in a short amount of time.

What are China’s motivations for international investment? Researchers suggest China’s motivations include securing natural resources, stimulating economic growth, reducing unemployment and improving China’s image and influence abroad. As a growing economy, China has secured access to energy by investing in countries with natural resources and ensuring that in return it receives licences to remove energy or natural resources. There are now over 1 million Chinese workers in Africa, and China has been criticised for reducing its own unemployment by using Chinese workers instead of local workforce on mining and infrastructure projects in Africa.

The American Washington Post believes another motivation for China’s investment abroad is to “build political heft.” But what level of influence does China have in the countries it invests in? On paper, China is not overly concerned by the internal affairs of its investment countries, but off paper there are many cases of China pushing its own agenda or asking investment countries to tow their party line. In Hong Kong, China’s biggest investment country, China is supposedly behind the plan to prevent the opening of the Tienanmen Massacre museum, a museum which documents the occasion when China opened fire on pro-democracy protesters.

The measure of China’s influence is whether it can persuade a country to do something it might not otherwise choose to do. China has frequently put pressure on other countries not to recognise or meet the Dalai Lama with some effect. South Africa, which has strong trade and investment links with China, was pressured to refuse a visa to the Dalai Lama twice, preventing him from attending Nelson Mandela’s funeral and Bishop Desmond’s birthday. The Norwegian government has recently announced officials will not be meeting the Dalai Lama when he visits next month. China previously severed economic ties with Norway after the Oslo-based Nobel Committee awarded the annual Peace Prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo in 2010. Many other countries that have not conformed to China’s recommendations over the Dalai Lama have faced retributions and damaged bilateral relations.

China can also be shown to have an effect on internal and regional decision-making of investment countries. For example, Cambodia’s dependency on Chinese investment makes it difficult for the country to criticise Chinese policies. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen has stated that the Chinese upstream damming of the Mekong river will cause no problem for Cambodia, a fact disputed by environmentalists and other South East Asian countries. In South East Asia the concern of upsetting China and damaging relations is such that diplomats report delays in decision-making at regional meetings as member nations quietly analyse Beijing’s potential reactions. A diplomat at the East Asian Summit reports, “China has been throwing its weight around and buying the loyalties of some Asian states. Some are easily swayed by money. If they see cash, they easily throw away their principles.”

Print

Print Email

Email