Sikyong Lobsang Sangay, the de facto Prime minister of the Tibetan Government in exile, said in Dharamsala on August 21, “The Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) cannot prevent any Tibetan from applying for the Indian citizenship”, thus confirming that Tibetans living in India can apply for Indian citizenship and the CTA will help them by providing supporting documents.

He continued, “The decision to apply for Indian or any other country’s citizenship is a personal choice. The Indian Citizenship act of 1986 grants citizenship rights to Tibetans born in India between 26th January 1950 and 1987,” He also added, “at the same time, the CTA cannot compel Tibetans to apply for the Indian citizenship”

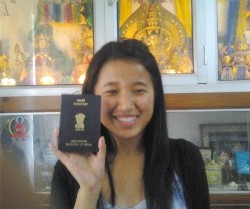

The Delhi High Court declared Namgyal Dolkar Lhagyari an Indian citizen by birth and issued her an Indian passport in December 2010.

Photo: Phayul

According to the Indian Constitution, Section 3, Citizenship by birth: every person born in India, (a) on or after the 26th January, 1950, but before the commencement of the Citizenship (Amendment) act, 1986 (51 of 1986); and (b) on or after such commencement and either of whose parents is a citizen of India at the time of his birth, shall be a citizen of India by birth.

Tibetans acknowledge that India has been incredibly generous in her treatment of Tibetan refugees, as has Nepal in the past. Currently, exiled Tibetans in India are considered “foreigners”, lacking even the protection of being officially designated as “refugees”. This raises the question of how the Tibetan people and their exiled government plan to protect themselves if political circumstances cause them to remain in India for another generation or more? India has not ratified the refugee convention, and has chosen not to extend full civil rights to stateless individuals living on its soil. As “foreigners” they are “guests”, and guests can always be asked to leave.

Examples of the questions facing the exile Tibetan community are: What if India places greater restrictions on the CTA in order to smooth relations with China? What if India starts to question the benefit of hosting an administration-in-exile run by a group of stateless refugees? What if India simply starts shutting down the CTA’s political components? It is to be hoped that the situation in India will never deteriorate as it has in Nepal, but the fate of the Tibetan community could be out of its own hands. It is this fundamental vulnerability that drives the strongest argument for Tibetans accepting Indian citizenship. Most pressingly, the reality is that Tibetan refugees – including the Tibetan Government-in-Exile (TGiE) – exist in India only with the continuing tolerance of the Indian government. As long as Tibetans remain merely stateless foreigners rather than citizens, India’s policy can change… just as Nepal’s did.

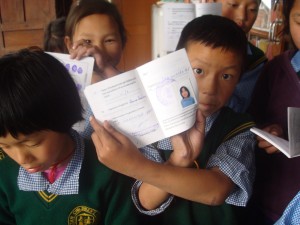

Tibetans contributing Chatrel, or Tibetan tax, are issued with a Green Book. This book has over the years effectively become the passport of exiled Tibetans, allowing them to claim their rights from the CTA. And in future it will become a base to claim Tibetan citizenship. Today, it is used for school admission, school or university scholarships and employment within the exiled community. Payment of the voluntary contribution is a condition for gaining voting rights in parliamentary elections.

What about Tibetan people in India who only have a Registration Certificate (RC – Indian registration for people with refugee status)? Currently, Tibetans in India must generally show their RC in order to get a Green Book and other benefits, for example, most scholarships awarded by the TGIE and admissions to Men-tse-khang (Medical Institute) and Sarah Institute (Buddhist studies) generally require an RC. This raises the question of whether the CTA/TGIE want to limit these benefits only to truly stateless refugees rather than Tibetans with Indian Citizenship?

Print

Print Email

Email