The building sits on the side of the road and if it weren’t for the yellow board, my gaze would have gone right past it. I walk up a small flight of steps that seem rather unassuming. As I push open the glass door, I see several desks, computers, and people going about with paperwork, often engaged in conversation.

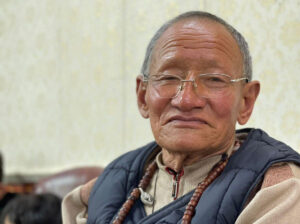

My request for an interview is met with enthusiasm and a simple dignity that makes me want to know more about the current office bearers of the Tibetan Youth Congress [TYC]. I sit down with Tenzin Lhamo and Tenzin Norzom; the information secretary and a researcher for the TYC. They have just taken up their roles a few months back after contesting in the elections and will be holding office for the next three years.

We sit in their conference room filled with plaques, certificates, and photos of the previous office bearers starting from the founding members. The four men I see on the very first photo started the TYC because they believed it was the way forward for gaining independence. Bringing together the Tibetan youth was important and a strategic imperative for the Tibetan story and struggle to have more torchbearers.

While gaining independence was the primary goal in 1970, since then the TYC’s vision has expanded to take into account the mass cultural genocide happening in Tibet. With rampant destruction of monasteries, suppression of Tibetan language and culture, and denial of religious freedom the TYC now works to create awareness on the same.

At present one of their main goals is to promote and preserve Tibetan tradition and culture in the face of the 21st century. While social media is often the conduit for creating awareness today, in the 1970s, the lack of technology meant travelling and forging relationships with the Tibetan community, colleges, students, and student leaders in various parts of the country. This involved demonstrations, protests, public speaking and, more centred around the situation in Tibet, the responsibilities of the youth and their role in the struggle for independence.

At the start, the TYC was the only organisation within the exile community and received incredible support from the Tibetan Parliament-in-Exile and His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Everyone involved believed that this was the way forward for independence. However, during the third tenure, His Holiness began speaking about “The Middle Way” approach and the Tibetan community saw the value in that. The TYC faced an uphill road as they believed it was one of many ways independence could be obtained. But, by taking a stand that was different from His Holiness, they drew a lot of questions, flak, and criticism and were tagged as anti-Dalai Lama by the public. This proved to be a major challenge in getting the momentum going again.

The entire Tibetan community believes independence is their birthright and the differing viewpoints in the approach to independence stems from a deep distrust of the Chinese government and policies. Seeing the changes happening in Taiwan real-time, the TYC believes they won’t do well under Chinese rule and want complete autonomy. However, they understand that there are different perspectives and respect the varying approaches as it unifies the community towards a single goal.

Despite having come this far, their application to join the United Nations has been rejected each time. They believe the Chinese presence at the UN is a large impediment. They recently organised a protest at the UN in Geneva when it was China’s turn to speak at the Human Rights Commission.

Their conviction stems from the historical evidence that Tibet has always been a free nation. Starting with 13 regional chapters, the TYC worked for the preservation of Tibetan culture. Fast forward to today, they organise grass-root level training for Tibetan youth in addition to exhibitions and political rallies, with an international network of collaborators. In every hunger strike, exhibition, movement and protest for independence, they say there will always be a TYC presence.

In an effort to encourage and promote education, the TYC recognises and rewards toppers from different streams, colleges, and schools. They also organise Tibetan language competitions and cultural fests. Based on interacting with them and seeing their work, I am inclined to believe that there is no single grand gesture, but a series of small ones to bolster faith, create awareness and change things. In keeping with the theme, they wear the chupa to work because they see it as a tangible part of their culture and don’t see it as only important during festivals and special occasions.

Additionally, they are constantly in touch with the Tibetan language, using it for all official communication whether on their letterhead or on social media. Except for press releases, all communication is in Tibetan and they see this as a celebration of their biggest conduit to culture: their language. Even on social media, their posts are always in Tibetan accompanied by an English translation.

Representing as they are a large portion of the Tibetan community, they are very aware of the social responsibility their words and actions carry. They see social media as a way to reach members of their community while contextualising the struggle for the 21st century.

Currently having 88 chapters around the world, the TYC has grown from a modest beginning to being recognised by, and affiliated to, several international and national organisations. Several of their activists have been jailed, but they still persist. With a modest salary, the TYC staff work zealously because they believe in the cause. The price, however, is having being born outside Tibet and never having been there, but yearning to go and see what their parents and grandparents saw, cherished, and called home.

They sign off with “If not now, when? If not you, then who?”.

Print

Print Email

Email