How much suffering does it take to wipe a smile off someone’s face forever?

Ven Bagdro’s body still bears the scars from Chinese torture chambers, he still sees as though it were yesterday his baby sister dead, his fellow monks slaughtered, the look in his mother’s eyes as they said their final goodbyes.

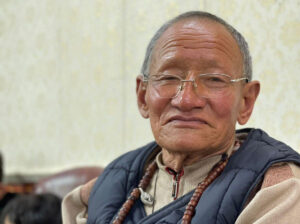

But his smile is real and warm. It reaches his eyes and lights up his face.

Born in 1970 to poverty-stricken parents in a village near Lhasa, Bagdro spent much of his childhood in the Tibetan capital begging for food. His family had small business selling incense but it was branded “un-communist” and closed down.

He was 13 when his sister died, and with the whole family wasting away he was merely starvation’s first victim. It was the monk’s bowls of steaming food, not Buddhism, that initially drew Bagdro to Ganden Monastery.

He remembers his time there fondly, but despite being surrounded by learned monks and Buddhist scriptures he remained ignorant even to the existence of the Dalai Lama until a chance encounter with two American tourists.

“I was 17 and had been a monk for a year when a lady handed me His Holiness’ book My land and My People. She told me that the Dalai Lama was my leader. I refused to believe it– my leader was Mao, I was a communist, loyal to my motherland China. After I read it I couldn’t stop crying. It was the first time that I had heard the truth.

“I knew then that I had to do something. I wrote to my parents asking them not to cry if I died. I was prepared to give my body, my blood to help reclaim my country. Then I went to demonstrate in Lhasa.”

For their disobedience Bagdro and his fellow monks paid the ultimate price. The march became a massacre, crimson robes turning a darker, far more ominous shade of red as Chinese soldiers poured in from all sides and bullets ricocheted off the temple walls.

“I saw child monks picked up and chucked off the monastery rooftop like sacks of flour. I was shot in the leg, and as I lay on the ground I saw a mother breastfeeding her baby. They shot her through the heart, straight through her child and into her chest.” Amid the onslaught of bullets Bagdro somehow managed to get away, living as a fugitive for months before news of his parents’ suffering drove him out of hiding. The Chinese authorities had been to his home, held a gun to his father’s head and threatened to arrest them if they didn’t give him up. When it came to a prison sentence it was either him, or them. They were guilty by association, tainted by this rebel monk who happened to be their son. Naturally Bagdro chose himself.

“In prison I was questioned over and over again: ‘Who are you working with? How much did the Dalai Lama pay you to protest? Where are your accomplices?’ After every question they would hold an electric shock weapon to different parts of my body. Head to mouth to genitals and back again. Round and round.

“I still refused to give up the names of the monks who had escaped. So then they removed my shoes and put my feet in ice. I was made to stand there for hours. When I stepped out all my skin peeled off – like a mango.

“This happened every day, and when I wasn’t being tortured I was left in a prison cell little bigger than a coffin. I tried to kill myself many times. I tied the rags I was wearing round my neck but the guards always caught me before I could die. ‘You can’t kill yourself. We will kill you, slowly,’ they said. The female guards would laugh and then stub their cigarettes out on me.”

Bagdro talks matter of factly. There are no tears in his eyes, no hatred in his voice. Does he never feel consumed by rage?

“I used to. When I arrived in India I was granted an audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. I was so angry. I wanted to kill them all. His Holiness hugged me and said that with violence I would achieve nothing. It was only through education and peace that things would change.”

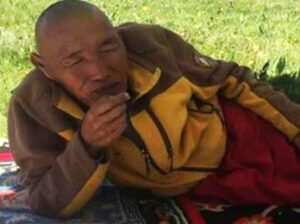

Two prison transfers later and weighing less than 39kg, Bagdro had been released. He hadn’t reached the end of his sentence, he was simply so close to death that the Chinese wanted him off their hands.

“They don’t like people dying in prison because then Amnesty steps in and asks questions. But I survived. I lived and I made it all the way across the Himalayas to India.”

Heeding His Holiness’s advice, Bagdro has turned to education to fight against Chinese rule. From his home in Dharamshala he has written five books, the most recent of which documents Tibet’s history: a cultural legacy that China is trying to erase.

And most of the time he is happy. His indomitable will shines through. “My love for my country gives me courage. I am so proud of Tibet and of my countrymen. They are so strong. They never give up.”

Bagdro’s smile is proof enough of that strength. Proof also that one day, Tibet will be free.

Ven Bagdro’s books include A Hell on Earth and Life in Exile which are available in Dharamshala and online. His latest book Tibetans shall be happy in the Land of Tibet, Chinese shall be in China, which is a collection of historical documents, was released in June this year.

Print

Print Email

Email