‘They didn’t understand that people never forget who they are’

Soepa talks about his experiences as a political prisoner in Tibet

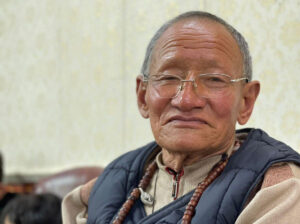

In a room where framed photos speak of mass protests, labour camps, torture instruments, hospitalised victims of police crackdowns and blood-stained clothing, I sit opposite a smiling man with deep wrinkles in which a painful past is quietly folded away. ‘We start?’ he asks.

Soepa, whose other name is Phuntsok Wangdu, tells me he comes from a nomad family in Mangchoe village in the Kam Region of East Tibet and was arrested when he was 24. Sentenced by the Chinese authorities to five years imprisonment for distributing Free Tibet fliers, he was taken to Drapchi prison. There he joined 400 other ‘political’ prisoners, an equal proportion of men and women, with some as young as 15. One of his closest friends, Jamyang Thinlay, was arrested on the same occasion and died a year into his sentence, aged 26, as a result of brain damage from the beatings by the guards.

Wary of sounding insensitive or voyeuristic I am reluctant to probe about Soepa’s own experiences of torture within the prison. However, unprompted and with extraordinary detachment, he tells me about everything he underwent in horrific detail. He explains to me that they were tortured not just to extract information but in an attempt to destroy their identities – to change the kind of person they were and to create a new person with a different way of thinking. ‘But they didn’t understand that that can’t happen’ he says ‘People never forget who they are.’ I ask if there were ever moments when he lost hope. He answers with an unhesitating ‘No.’ None of them ever lost hope, he explains, because they knew they were fighting for the truth. ‘We lived under the Chinese flag but we always dreamed of our own flag flying high.’

His religious beliefs allowed him to withstand these traumatic experiences because according to Buddhist doctrine if it is not your time to die, you will not die and if it is, you must accept that.

I ask him how he views the prison guards who did such things to him and killed his friend. His response takes me by surprise. He tells me that he does not resent those guards because they had no choice. They did what they did not because they were sadistic or believed in it, but because they had to make a livelihood to support their families and because, if they didn’t, they themselves would be severely punished. The guards would even talk to the prisoners and tell them this. As Soepa goes on to explain, although the senior officers were all Han Chinese, the guards themselves were predominantly Tibetan. He believes that this was a conscious strategy by the Chinese authorities to undermine Tibetan solidarity.

Throughout our talk, I find it difficult to really connect the story being told with the person telling it in front of me. The horrors he describes seem to belong to the realm of fiction. We sit in silence for a few moments and he is the first to speak: ‘It’s all very well for people to say pretty words but we need something real to change. Every day still people are dying and being tortured for what they believe.’

He was reunited with his family after 5 years. With no communication permitted throughout his time in prison, they had been informed by the authorities that he was dead.

Print

Print Email

Email