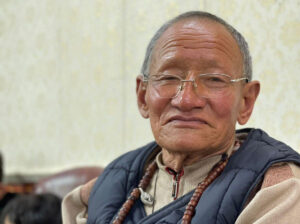

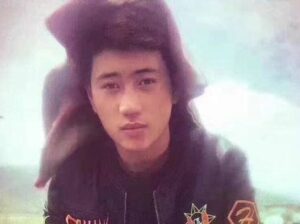

Wearing low-hanging green jeans, a bright Bob Marley hoodie, sunglasses, a flat cap and an enormous grin, Norbu swaggers into the cafe where we are meeting, stopping at every table on the way to fist-bump his friends. This carefully constructed image, however, is far-removed from the educated, passionate poet who cites Blake and Coleridge as his most important influences. Despite his westernised dress sense and lifestyle, in his poems he is deeply critical of the effects of modernisation on today’s society and tells me that, if he had the chance, he would give up everything and return to the Tibetan goat-herding lifestyle which has been in his family for centuries.

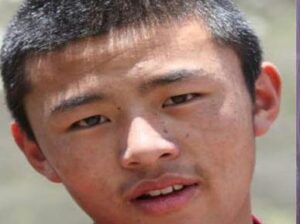

At the age of 6, Norbu moved away from his nomadic family in the remote Amdo province to Lhasa where he lived for the next 8 years. When I ask about these years, he tells me, ‘I was a bad guy then. But now I’m a good guy…’ – he pauses and grins – ‘half good.’ He explains that, when he was 12 or 13, he fell in with a gang of boys a lot older than himself. ‘We thought we were in one of those Chinese gangster films’ – they roamed the streets at night fighting other gangs, drinking and taking drugs. When I ask if they ever got in trouble, he seems reluctant to go into specifics but describes one occasion when the Chinese police took them in and tortured him for hours with wires which left deep, criss-crossing scars all over his body. ‘They were drunk,’ he says. ‘I could smell it on their breath when they leant over to beat me.’ Despite these run-ins with the authorities, he tells me he had no opinions at the time on the Chinese occupation of Tibet or the Dalai Lama, due partly to his lifestyle and partly to heavy censorship. ‘In Lhasa I was a little baby. I knew nothing.’

At the age of 14, his Uncle decided that there was no future for him if he stayed in Lhasa, so arranged for a guide to lead him and his 8 year-old sister over the Himalayas to Nepal. The journey took over a month, walking by night and sleeping during the day to avoid detection by the Chinese authorities. If they heard a vehicle approaching they would jump off the side of the road without seeing where they were going. He starts giggling uncontrollably at the memory – ‘sometimes we would just be rolling and rolling down in the dark not knowing when we would stop!’ Their guide turned out to be an alcoholic and stole Rs 200, the only money they had, from each of them but they made it to Nepal.

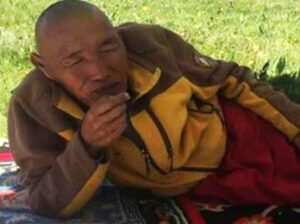

Since arriving in Dharamsala, Norbu has completed 5 academic years in the space of 2 and attributes his change in attitude to the teachings of the Dalai Lama as well as reading anything he can get hold of from Shakespeare to Paulo Coelho – ‘you can learn more from books than you can from people’. He has written an entire book of poetry in Tibetan under the pseudonym of ‘Ghost Eye’ which he hopes to publish when he leaves school. Most of his poems are political, advocating complete Tibetan independence and a return to the past. He opposes the non-violent ‘Middle Way’ autonomy plan of the Central Tibetan Administration. But he also writes about nature and shows me a beautiful little poem he has written in English about a mountain stream. ‘I like writing about nature because it is always more powerful than humans. The Chinese government can crush any physical uprising but it can’t crush the forces of nature. It is the same with our spirit.’

It has been 6 years now since he last saw his parents and I ask if they’re proud of his poetry. ‘They don’t know about it,’ he answers. ‘It’s too dangerous to talk about it on the phone. If the Chinese authorities are listening in on our conversation, my parents could be arrested and tortured.’

Although he is trying to write more poetry in English, Norbu is far prouder of his Tibetan writing. As I flick through his Tibetan poetry, I ask him what one short title means. ‘You can’t say it in English,’ he says and thinks for a while, trying to explain – ‘it means that the roof of the sky is not big enough to cover a Tibetan heart.’

Coffins of Black

By Ghost Eye

When my country was lost, I was born.

Though our ancestors from us are torn

Their spirits live on, these Lapchen* Warriors

And we will keep struggling in their honour

As the Eastern Dragon’s paw stretches over my land

Rangzen** is manacled in cast-iron bands.

Yet we stand together: day by day, year by year

Our fight will go on till the drying of tears

In Tibet; a terrible sight

People set fire to themselves for the right

To freedom of worship, of speech, of choice;

In the fields of justice we shall raise our voice

Nothing to fear, nothing to bear

Just lift your fist, shouting in tears;

Rangzen! Rangzen! Rangzen!

No more to wait for our liberty back.

No more to live in coffins of black.

*Noble

**Freedom

Print

Print Email

Email