Mariko could have stepped off the streets of London as she sashays into Kunga’s guest house, hips swaying, pout in place.

Mariko could have stepped off the streets of London as she sashays into Kunga’s guest house, hips swaying, pout in place.

She has lips no money could buy, and a face so feminine you wonder how she could have been born a boy. “Oh when I was a kid I was always very feminine,” she tells me. “The way I played and danced, it was all like a girl. My friends used to tell me when you are 18 you will become a girl and now the same people say look, we were right!”

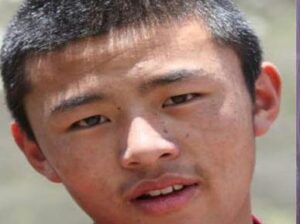

But it was not until June last year that Mariko became the woman and much-loved local celebrity she is today. She was born Tenzin Ugen in Bir, to parents both of whom worked in the local school. Her family lived on the school grounds, for all practical purposes an excellent set up, but one which Mariko found suffocating.

“For me and my younger brother, we were there in the same place the whole time. For nine years I never left school. Every holiday other kids would travel home, or go away, taking trains, buses, cars. I was so jealous, it all seemed so exciting to me. So when my dad told us that we were both going to become monks in Darjeeling it sounded like a vacation. I didn’t stop to think that I wouldn’t be coming back.”

Mariko’s near-perfect English with an American twang is telling of the western fashion programs she loves, and growing up half a world away has by no means hampered her sense of style. She shows me – on the latest iPhone – pictures of her both in trousers and traditional Tibetan chupas, her photos pulling in more than a thousand Facebook likes…on a slow day.

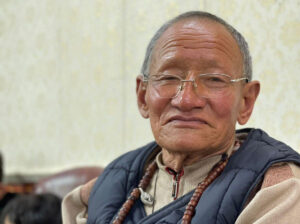

She does not resent her father for sending her away, gushing about the sound moral grounding monastic life gave her. “They teach you so many positive things: how to be a good person in your life, how to respect others, how to be honest. I am realising now that I am the person I am because I was given that knowledge when I was a kid.”

When she was 14, Mariko graduated from Samdrub Darjay Choling Monastery and moved to another in Nepal to continue her studies. But she missed her family. She hadn’t seen, and had hardly spoken to her parents for five years. They had moved to McLeod, her brother had gone home before her, and she longed to be a part of their new life. She ran away, catching a bus to Delhi, another to Dharamsala, and after wandering the streets for what felt like hours, stumbled across an old family friend who pointed her in the direction of home.

Her decision to stop being a monk took three years, intertwined as it was with her growing desire to become a woman. She lived at home, and free from the rules that govern monastic life, began to embrace her femininity more and more. “Everybody thought I was a nun,” she explains. “All my clothes were so fitted, and so clean, always pressed. So many people got confused.”

Her decision to stop being a monk took three years, intertwined as it was with her growing desire to become a woman. She lived at home, and free from the rules that govern monastic life, began to embrace her femininity more and more. “Everybody thought I was a nun,” she explains. “All my clothes were so fitted, and so clean, always pressed. So many people got confused.”

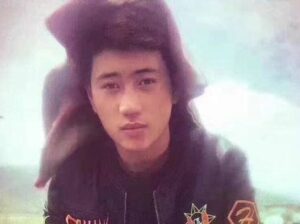

A friend’s wedding party was the catalyst that pushed Mariko to finally renounce her robe. The celebration was in Delhi, no one from McLeod would be there: it was the perfect place to give being a girl a test-run. She swapped her robe for a dress, sandals for stilettos, and wearing a wig and a lipsticked smile, did not leave the dance floor.

Wechat turned out to be both her downfall and her salvation. On returning to McLeod, Mariko realised that the game was up. The whole town had seen a video of her dancing and though she vehemently denied that it was her, no one believed it, forcing her to think about what she truly wanted from life.

“Do what makes you happy,” her parents told her. So she disrobed. But it was almost a year before she mustered up the courage to publicly declare herself a woman. “I wasn’t a monk anymore, but I was still not how I wanted to be. For eight months I was like, I don’t know what to do, at that time I couldn’t move forward in my life. I felt completely stuck.”

“Then in June last year, my friends persuaded me to dance in the Miss Tibet pageant. It was amazing, and afterwards I was like, yeh, this is me Mariko right now.”

And this is without a doubt “Mariko right now.” She overflows with happiness and confidence. Her fan base grows daily, Tibetans clamour for her autograph, and tickets to her dance shows sell out every time. It is the show of support, not the fame, however, that means most to her.

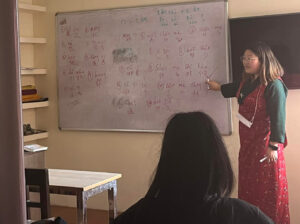

Only 18 years old, Mariko lives in the moment, practicing her dance, teaching makeup classes and generally having fun, but she is also strangely wise.

“You only get this one life,” she tells me. “The past is done, so forget it, the present is right now so live it with no regrets, and the future is yet to come so dream it. When you’re eyes are shut that is it, it’s finished, so don’t be afraid to be yourself.”

Print

Print Email

Email