Listen to the recording of this interview here :

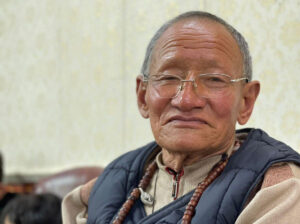

Lhasang Tsering at his residence in Mcleod Ganj

Photo: Contact / Sonam Paldon

Lhasang Tsering has been an outspoken advocate for Tibetan independence for half a century.

Since turning down the opportunity to become a doctor in the United States in the early 1970s, Lhasang has gone on to live a kaleidoscopic existence worthy of a mandala.

In this interview, Lhasang talks about his childhood in Tibet; his coming to India; his experiences with the Tibetan guerrillas in Mustang; the Tibetan independence movement in the 1970s and 80s and his decision to speak out against His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way policy in 1989.

Lhasang’s new book No, Your Holiness, No! – Saying “No” to His Holiness the Dalai Lamais finished and due to be published when the coronavirus lockdown is lifted. Until that day Lhasang spends his time on his balcony at Exile House in McLeod Ganj, gazing towards his lost homeland across the snow-capped Himalayan peaks.

This interview was recorded on May 2, 2020.

Contact: Tell us about your early life in Tibet.

Lhasang Tsering: My late father was a tantric lama from eastern Tibet who had settled in the west. I was born in western Tibet and had a privileged childhood. Although the Chinese invasion had taken place the Chinese had yet to come to western Tibet. So, I had a privileged childhood. I remember clear open blue skies, vast open spaces. Whenever I think of those few short years I spent in Tibet, tears come to my eyes. It’s a place that I miss.

Contact: How about your move to India, how did that come about?

Lhasang: As I said my late father was a tantric lama and he had two premonitions. Firstly, of his own early death, and secondly, he feared a national tragedy. Sadly, both came true. Before he died, he took us on a pilgrimage to India, to the land of the Buddha. Most Tibetans couldn’t make it in those days, but it’s the dream of many to make this once in a lifetime trip. So, my late father brought us to India, we did our pilgrimage to Bodhgaya, and then he passed away at a holy lake called Rewalsar*. So, when people ask me “When did you come to India?” I say “I didn’t come to India, my parents brought me here.” I was seven years old.

*Rewalsar is a holy lake in Himachal Pradesh associated with Padmasambhava [Guru Rinpoche, who brought Buddhism from India to Tibet in the eighth century].

Contact: Where did your family settle?

Lhasang: When my father passed away, and this memory is very clear despite the many years that have passed and my stroke, he was cremated on the banks of Rewalsar. I remember a huge funeral pyre and my late mother performing the prostrations. While we were observing the 49 days of prayers after his death the other refugees came from Tibet with His Holiness.

At that time the Indian plains were a little too hot for us Tibetans. We did not have skills for the Indian job market. Most Tibetans at that time were employed as road labourers, I was in a road labour camp in Manali. After His Holiness settled in Dharamshala in 1960, some officials came and picked us up.

My eldest brother decided “mother is alone, I will take care of her,” I still feel grateful for that. My other brother and I were brought to the Nursery for Tibetan Refugees, which today is called the Tibetans Children’s Village (TCV).

Contact: How did your schooling progress?

Lhasang: I was among the first group to be sent to a Tibetan refugee school in Mussoorie. This was the first Tibetan school in India. While I was in that school some American missionaries from a group called “TEAM” came to the school and conducted a few IQ tests. Along with another boy and a girl I was sent to a privileged public school called Wynberg-Allen in Mussoorie. It was founded by the British in 1888.

Contact: There was some talk about you becoming a doctor in the United States. Tell us about that.

Lhasang: When I was in Class 8 in school the English language teacher had a habit of making us write a composition. One week the topic was “My Ambition.”

By then I had read an article about Tibetan guerrillas fighting in Tibet in an issue of the Reader’s Digest and I had made up my mind that I must join them. I thought “these are the same people who fought when the invasion took place”. But there was no information about younger people joining them. I thought,“if younger people don’t join how will the struggle continue”.

But I wasn’t going to state this ambition in my school essay, so I made something up! I wrote that I wanted to become a doctor. I wrote that Tibetan hygienic habits were not good enough for the hot climate in India and also that refugees were facing difficulties from diseases that did not exist in Tibet.

To cut a long story short, I wrote this one essay about wanting to become a doctor so everyone decided, “Lhasang is going to be a doctor.” So, when I completed school, I was offered a scholarship to study medicine, but I had already decided to join the guerrilla force and I refused.

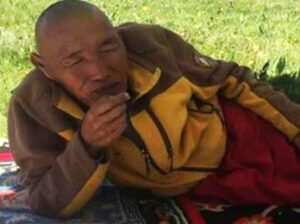

Contact writer, Ben Byrne with Lhasang Tsering

Photo: Contact / Sonam Paldon

Contact: You famously fought in Mustang with the CIA backed Tibetan guerrillas. That army was disbanded in 1974. What happened in the aftermath of that?

Lhasang: I was in Mustang through most of 1973. Early in 1974 I came back to Dharamshala because I was supposed to be sent for some special training. By then, you know, President Nixon had visited China and signed the Shanghai Communique. Although I have not seen this in writing, I believe that a part of the secret deal made in reaching that agreement between the US and China involved the CIA stopping their assistance for the Tibetan guerrilla force in Mustang. The King of Nepal had also been hauled up for a meeting with Mao and we guerrillas were facing pressure from the government of Nepal. The media was here in Dharamshala to ask His Holiness what he was going to do.

I went up to see His Holiness and begged him not to call off the activities of the guerrillas. But there were many factors at play. The situation was so tense. His Holiness decided to send a verbal taped message to the guerrilla force, asking them to suspend their action.

When that first message was played in Mustang, two of my friends…they committed suicide. They could not disobey His Holiness because they could hear his voice on the tape. They could not give up because they had vowed to fight for freedom.

A few others committed suicide, others wanted to continue the resistance, but the government of Nepal forced the remaining guerillas to surrender.That was the end of the active struggle for freedom. Now we are the most successful refugees in the world, but I am not proud about that. We have failed as freedom fighters, that is my pain, and that is my problem.

Contact: What did you ask His Holiness when you went to see him about the guerrillas?

Lhasang: My request to His Holiness was “please don’t get involved, we cannot give up the struggle for freedom because this is about the life of the nation.” However, His Holiness chose to end the guerrilla’s activities. I’m not blaming His Holiness for that. There were huge diplomatic pressures on him.

Contact: Talk about your relationship with Jamyang Norbu [former guerrilla fighter, Tibetan activist and writer] and how the Rangzen movement [movement fighting for Tibet’s freedom and independence from China] evolved in the 1970s and 1980s.

Lhasang: I had heard about Jamyang Norbu before I went up to Mustang because he had already served there for a year. He wasn’t there in Mustang at the same time as me, but before I met him personally, I enjoyed reading the huge number of books that he had taken to Mustang. From those books I got some idea about his interests. On coming back to India, I finally met Jamyang. By then he was a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Tibetan Youth Congress (TYC).

All through the 70s in Dharamshala there was this feeling of purpose driven by the first generation of people educated in exile. People like Jamyang, Tenzin Geshela, the late Lodi Gyari, Tenzin Namgyal, the late Mr Sonam Topgyal, who was the head of the government. There was this feeling of purpose and a sense of unity which today we lack.

Contact: What was this purpose that these people you mention had coalesced around? What was their common goal?

Lhasang: The common goal of struggling for freedom. A new generation had graduated from high schools and colleges in India. The CIA had stopped helping us but it didn’t matter. We were ready to carry the burden on our shoulders and to get into action. We knew that unless we had an active struggle for freedom there could not be support. Support cannot precede action; support can only follow action. So, there was this exciting new generation of leaders graduating and taking over responsibility from the older generation.

Contact: When did you conceive of your Mosquito Plan? Talk a little bit about that.

Lhasang: I came up with that idea in 1980 after I came back from Tibet. Around this time there was a lot of pressure on the Tibetan Government-in-Exile. Indira Gandhi [Indian Prime Minister at the time] was trying to get India onto the United Nations Security Council, but this was being vetoed by China. In 1979, in response to this pressure, His Holiness sent the first so-called Fact-Finding Delegation to Tibet. I was in Tibet at the time and thought that we were simply being misled by the Chinese. I came back and went up to express my views to His Holiness, but he would not listen. Then in 1980, when the second and third delegations went to Tibet, Jetsun Pema, the younger sister of His Holiness, asked me to take responsibility for the TCV schools whilst she was away. I refused because I had decided to go back to Tibet. When I returned to Tibet that time, among other things, I saw evidence of Chinese settlers moving into Tibet. Immediately I thought, “now we’re finished.” I cut short my trip, I had planned to stay for two or three years, but after I saw evidence of what I call “Chinese demographic aggression” or “China’s Final Solution” I came back to Dharamshala and asked His Holiness to appoint me as the head of the government. I said I could not achieve freedom in five years but I would mark out a clear way forward.

We don’t have a military solution. The Chinese army and armed police forces combined are bigger than the entire population of Tibet. We don’t have a diplomatic solution; the powerful nations of the world want to do business with China. So, what I call the “strategy of the mosquito” came about. The four nations under Chinese rule: East Turkestan; Tibet; Southern Mongolia and Manchuria would come together. One member from every family of our four nations would move into China. I just call them mosquitoes. If you have big powerful man with fancy guns locked in a room full of mosquitoes, machine guns are useless against mosquitoes! China may have nuclear weapons but you can’t use them against people in your own cities. So, what are these so-called mosquitoes going to do? Target communications and power supply. For a girl to cut a telephone wire, would we really need a UN resolution? If a young man were to throw an iron rod across high tension wires, without power what would the Chinese produce? If there is no power for a factory in Shanghai, who do they arrest in Tibet? If telephones in Beijing are not working, who do they arrest in Mongolia? These actions should be carried out in secrecy. I’ve been bitten by many mosquitoes, but none have left a visiting card! Some things are not to be spoken about. You go around speaking about peace in the West. Then you go and do these things in China, but don’t talk about them.

Contact: What was the reaction to this plan among the Tibetans?

Lhasang: Well, all I could do was request His Holiness to consider my plan. But he made his decision to send the fact-finding missions and then announce his Middle Way Approach. Then we were talking about negotiations with China. It takes two to shake hands. The Tibetan leadership has been extending its hand since 1979. But the Chinese have no need to shake the hands of helpless refugees. They want Tibet, they don’t want smelly Tibetans! They already have too many of their own people and the number of Chinese in Tibet is increasing every day, the number of Tibetans is decreasing.

Contact: You famously opposed His Holiness’ Middle Way Policy on the same day it was announced. Tell us about that.

Lhasang: I was in Geneva that morning in 1988 trying to get the diplomatic news from the United Nations. Actually, I just call it the United Governments. Tibet is a nation but we don’t have representation there. Anyway, I got a call saying the Daily Telegraph in London wanted to talk to me about this new policy that His Holiness had just announced. I hadn’t even seen it! I quickly read a statement on the policy and then the call from the Daily Telegraph came through. I stated clearly and firmly that the policy was not acceptable. Freedom is the life force of a nation and you cannot give up on life.

The older generation of Tibetans were shocked and dismayed that I had disagreed with His Holiness. I believe there were even campaigns to sign up volunteers to eliminate me. But in general, among the thoughtful public, especially among the younger generation, there was support for me. One clear piece of evidence that there was support for my position was that I was re-elected by the Tibetan Youth Congress in 1989 with 89.9% of the votes, a bigger majority of the votes than I had previously received. There was clearly public sympathy for my position.

But this is not a question for the people in exile. My view is that the people inside Tibet are voting for freedom with their lives through self-immolations and other actions. This is the vote that I respect.

Contact: You’ve written a poem called Thank you India. Speak about your feelings towards India.

Lhasang: With regard to India, first of all our [Tibetans] most precious possession is the Dharma and it came to us from India. Our written script was also adapted from Sanskrit. And today, more than in the past, with our own homeland under China’s occupation, the government and the people of India have given us a second homeland. We are able to preserve our own culture and religion and enjoy more freedom here than our fellow Tibetans in Tibet. To that extent I feel forever indebted to the government and the people of India.

Contact: You’ve written five books of your own poetry and you’ve translated the Sixth Dalai Lama’s poems. Speak about the authors who have inspired you.

Lhasang: Wordsworth and Tennyson. In terms of non-fiction, Thomas Paine, his book Common Sense was a great inspiration. Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy. And also, at a political level, Dee Brown with Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. These were books that gave me a sense of purpose. Yet, as inspiration for my own writing and expressing myself in verse, the local JJI Exile Brothers [a Dharamshala-based band of Tibetan musicians] verse has this advantage of being set to a tune, so you reach a wider audience.

Contact: You have a new book ready to go, what is that about?

Lhasang: Most people know by now that I was the first person to say “No” to the current Middle Way Policy. Before that, after graduating I said “No” to a scholarship for studying medicine in America. Later on, I said “No” to His Holiness when he asked me to serve as his private secretary. In short, I have said “No” to His Holiness on five major issues. But he has also declined my suggestions on various occasions. So, this book documents all of those occasions, these various disputes over the years. I also said “No” to a million dollars offered to me by the Mongolian and Tibetan affairs bureau in Taiwan. They wanted me to work for them, I said “No”.

Contact: What did they want you to do for them?

Lhasang: I didn’t accept the offer of a million dollars, so I never came to know what they wanted me to do.

Contact: So, what’s the title of your new book and when will it be published?

Lhasang: It’s called No, Your Holiness, No! Saying No to His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The book is ready I’m just waiting for this lockdown to be over and then I will go down to Delhi and we will see what happens.

Print

Print Email

Email