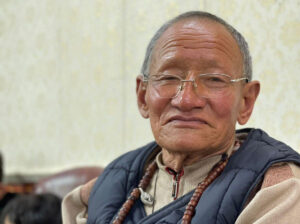

Lobsang Rabsel, who prefers being called Rabsel, has worn many hats within the Tibetan community since he first arrived in Dharamshala over twenty years ago. Now the busy proprietor of Common Ground, a charming restaurant serving up a diverse range of food from Taiwanese dishes and Tibetan staples to vegan desserts, Rabsel leads quite a different life than the one he left behind in Tibet.

Lobsang Rabsel, who prefers being called Rabsel, has worn many hats within the Tibetan community since he first arrived in Dharamshala over twenty years ago. Now the busy proprietor of Common Ground, a charming restaurant serving up a diverse range of food from Taiwanese dishes and Tibetan staples to vegan desserts, Rabsel leads quite a different life than the one he left behind in Tibet.

As we sit across from each other at an outdoor table at his café, Rabsel begins telling me about his life. Occasionally he laughs—a laugh that seems to begin deep within his throat and gradually gathers joy as it’s released. Born in 1972 in Namtso to nomadic parents, Rabsel grew up with an array of livestock: yaks, goats, and sheep which he helped to take care of as a youngster. Along with his five sisters and two brothers, the youngest son of the family explains that he enjoyed his early years migrating every couple of months to new areas of the grasslands lying below Tibet’s zari, or rocky mountains that were ever-looming off in the distance. When discussing his family’s nomadic lifestyle, Rabsel states, “It has a beauty and it [also has] challenges.”

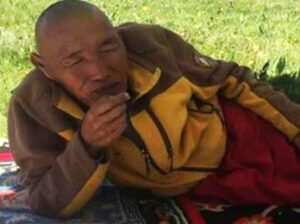

Rabsel reluctantly left his family’s village at the age of eight or nine to begin attending a boarding school, followed at eleven years old with a Chinese school. Then fourteen-year-old Rabsel entered a monastery where he became a monk until he was nineteen. During his time there, Rabsel increased his knowledge of Buddhism and learned lessons about reducing attachment and negative energy. Even today, he puts into practice what he learned about compassion and tolerance. “It [Being a monk] gives me [a] chance to think–you know–why . . . how we can be useful in life . . . not about making money. It’s more about, like, spiritually, how you can [be] happier.”

Rabsel’s Common Ground Cafe and Restaurant

Rabsel’s desire to leave Tibet was fuelled by his growing awareness of the situation developing between Tibet and China. “The Tibetans, like, spiritually we [were] kind of doing very well with that–you know–monks, nuns, lots of practitioners . . . many scholars; but unfortunately, [at] the political level, we [were] very bad. We didn’t have much knowledge about the other side of the world.” As the Chinese began creating “re-education” programmes within schools and monasteries, Rabsel and a friend were captured for “show[ing] disobedience”. They were beaten and held in custody for an entire day. Rabsel recalls being told by the officials, “If you’re trying to kick the sky, your eyes [will] break [into] many thousand[s] [of] pieces [and the] sky will fill up [with] blood because the Chinese communist government is [as] high as [the] sky . . .a very powerful country.” Not long after, he began planning his escape.

In 1993, Rabsel arrived in Nepal where he stayed for a month until the Tibetan Reception Centre organised for him to enrol in classes at a transit school in Dharamshala. By the end of 1995, he left his school, following which he took up various jobs at restaurants: manager, assistant manager, dishwasher, cook, baker, etc. He even met his wife, who was studying sewing at the Tibetan Women’s Association, at one of the cafés where he was employed. He says of those early years working in hospitality that, “I worked in the cafés [from] six in the morning [until] close to eleven thirty in the evening.” His penchant for hard work paid off though when he was given the opportunity to begin running a local café called Common Ground owned by a Tibetan and Taiwanese–American couple with whom he was friends. Starting a business wasn’t without its difficulties. “I used to say I started at zero, with no family support, no formal education, [and] no business education.”

Rabsel became involved with Lha Charitable Trust, first as a volunteer from 2000 until 2008, then as an employee when he was appointed Volunteer Coordinator. His tasks were to provide volunteers with information about the Tibetan community and what to expect from their experience. Three years later, he was promoted to Deputy Director. He says, “I gained a lot of knowledge about international [communities and] what kind[s] of systems they have.” He left Lha earlier this year after ten years of dedicated service.

Rabsel became involved with Lha Charitable Trust, first as a volunteer from 2000 until 2008, then as an employee when he was appointed Volunteer Coordinator. His tasks were to provide volunteers with information about the Tibetan community and what to expect from their experience. Three years later, he was promoted to Deputy Director. He says, “I gained a lot of knowledge about international [communities and] what kind[s] of systems they have.” He left Lha earlier this year after ten years of dedicated service.

Nowadays, in addition to running Common Ground full-time, Rabsel makes time for his wife and two daughters about whom he says, “It’s nice to be with family sharing the love and happiness together.” Although he has had to make enormous personal and professional sacrifices to reach this point in his life, Rabsel declares, “I have no regret[s] at all in my life. I . . . challenged [the communist regime] when I was seventeen years old . . . I’ll still sometimes be proud. My life’s not empty.”

Print

Print Email

Email