I meet Kunsang outside Tibet Hope Café, and we walk up the hill to Café Budan. On the way, we gather a following of dogs. Kunsang gets me a chai, orders an Americano for himself and then disappears. He returns with three packets of biscuits which he breaks up for the dogs. It is an odd sort of community he has going here. “This one,” he says, of the black dog curled up at his feet, “is very naughty. Used to follow me everywhere. Pee on everything, including the shawls outside shops. Angry shopkeepers would come out and say, Is this your dog? And I would say” — he folds his hands in a gesture of open, boyish sincerity — “not mine.”

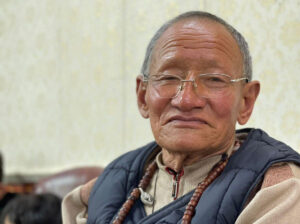

Kunsang is 28, young for the charity he runs: Tibet Hope Centre. McLeod Ganj was originally a pit stop; at 23, he was sorting out his visa papers to move to America, where his parents and brother were waiting for him. He wanted — still wants— to travel and make films. But a friend came into his house one day, and asked if he would help him with some English. Then the friend brought a friend who brought a friend. Why not leave? I ask. He smiles. “I am a lazy person. I like it here. And my friend, I could see how much he had improved. I could see the change in him. It made a difference.”

Running a charity is not easy, of course. Much less creating one. Left to himself, Kunsang would have happily taught without an official title, but his classes grew and there are rules in place for this kind of thing. There was a lot of running around, trying to find the right papers, permits, an official office. His family was confused by this new dream, by the son who stopped to get his visa and then never arrived. They understand now, he tells me.

What about the café? Kunsang shakes his head. The café came later, conceived as a good source of funding. Originally called Oasis Café, it was another string of careful negotiations, patience, and generous volunteer funding. I ask about the décor. I love the red low tables, and scattered cushions: the entire vibe is hippie and avant-garde. He laughs. “We made the tables ourselves. And cushions are a lot cheaper than chairs.” Tibet Hope Café was born.

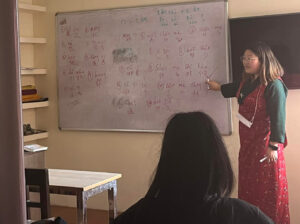

I know the café as the unofficial Tibet Hope Centre classroom; a place many volunteers treat as home, and where, on a lazy afternoon, you can find students and teachers alike, leaning over a low table, trying to understand English. It is where they have conversation classes: a single word with a list of questions. Change. Refugee. Topics that can broaden the mind. For that, ultimately, is Kunsang’s aim: to broaden the mind so that people can better connect. Ask him about his plans for his charity, and it becomes apparent that most of his ideas centre on community. The Tibetan community here is not unified, he explains. There are those who have just arrived from Tibet and those who have lived most, if not all, of their lives in India. Their ideologies are different. For instance? I ask. He thinks. Tibetans from India are more relaxed, he says. And those that come from Tibet, they obviously want to be around people like them, and understand them, to feel less alone. So they don’t mingle a lot with the Tibetans from India. But he hopes to change that. Currently, Tibet Hope Centre hosts a refugee talk every Wednesday, where exiles can come and share their experience, to foster greater understanding between all factions in a culturally diverse McLeod Ganj. In the future, he hopes to organize more events for the Tibetan community (“Volunteering in an old age home,” he suggests. “Or a mass clean up.”), to allow the different factions to bond. “And buy chairs for the café.”

I thank him for the interview. As I get up to leave, the dog lifts his head, alert and curious. Satisfied that no one of importance (i.e. Kunsang) is leaving, he settles back down.

Print

Print Email

Email