To many in the international community the COVID-19 crisis has brought into sharp relief the need to talk frankly about the nature of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) one-party state whilst being sensitive towards those who were the first to suffer; the Chinese people.

To many in the international community the COVID-19 crisis has brought into sharp relief the need to talk frankly about the nature of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) one-party state whilst being sensitive towards those who were the first to suffer; the Chinese people.

Whilst the COVID-19 virus continues to have a truly global impact Chinese officials are reporting that they have beaten the disease and are starting to ease restrictions. This presents a challenging situation to the wider international community where many people hold the People’s Republic of China (PRC) responsible for the outbreak. United States (US) President, Donald Trump, asserted that COVID-19 “could have been stopped in its tracks. Unfortunately, they [PRC] didn’t decide to make it public… the whole world is suffering because of it”.

Following the efforts to cover up the deadly SARS in 2003 early suspicions of a similar outbreak in Wuhan were shared privately on Chinese social media as far back as December 2019, only for those messages to be intercepted and the senders reprimanded by officials. Xu Zhiyong, a former Chinese law lecturer, summed up the PRC’s handling of COVID-19, writing in a February 2020 essay that “[the Chinese leadership] didn’t authorise the truth to be released, and the outbreak turned into a national disaster”. Xu is now reported to have been detained on a state security charge.

Kalden Tsomo speaking at UN summit

At the pandemic’s apparent peak in PRC the official classification system for COVID-19 data was forced to change in the face of mounting public suspicion that information was being suppressed. This resulted in a 10-fold increase in reported cases overnight. Speaking at a United Nations (UN) summit Kalden Tsomo, UN Advocacy Officer for the Tibet Bureau-Geneva, expressed doubt as to whether COVID-19 reporting for Chinese administered Tibet was reliable as recently as March, stating that, “the actual number of affected cases in Tibetan areas remains still unknown due to China’s crackdown on freedom of speech and absence of transparency”.

The level of propaganda generated by the Chinese authorities is also reported to be causing Western officials concern. Government sources in the United Kingdom have warned that China’s official statistics on the number of COVID-19 cases could “be downplayed by a factor of 15 to 40 times”. Meanwhile Reuters reported that PRC’s attempts to blame the US military for the pandemic by suggesting the US military might have brought the coronavirus to Wuhan have been described as an attempt to spread “disinformation” and met with “strong US objections” from US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo.

The level of propaganda generated by the Chinese authorities is also reported to be causing Western officials concern. Government sources in the United Kingdom have warned that China’s official statistics on the number of COVID-19 cases could “be downplayed by a factor of 15 to 40 times”. Meanwhile Reuters reported that PRC’s attempts to blame the US military for the pandemic by suggesting the US military might have brought the coronavirus to Wuhan have been described as an attempt to spread “disinformation” and met with “strong US objections” from US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo.

Despite Chinese attempts to sway public opinion and advance its own position, global strategy advisor, Parag Khanna, believes that “people… know exactly where this [COVID-19] came from, so you don’t need to worry about China winning any global narrative campaign”. Indeed by denouncing international criticism of their secretive response to COVID-19, PRC has received some public backlash. Reports that China’s ambassador to Nepal asserted that PRC “reserves the right to further action” over the publication of a critical article in The Kathmandu Post, resulted in Nepali media figures publishing a joint statement describing the action “as a direct threat to the Nepali people’s right to a free press, freedom of opinion and freedom of expression”. This incident was followed by PRC’s decision in March to expel foreign journalists; a move described by US publishers as “uniquely damaging and reckless as the world continues the struggle to control this disease, a struggle that will require the free flow of reliable news and information”.

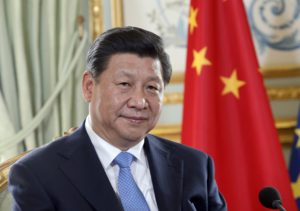

Photo: Xinhua

Neither the criticism, nor the virus itself, appears to have slowed Beijing’s determination to carry on as normal. Whilst quarantines were enforced across much of PRC, Chinese police forged ahead with a campaign to send a “million police into 10 million [Tibetan] homes” reportedly in an effort ensure PRC police “are in close contact with the masses”. Additionally, as far back as February, it has been reported that infrastructure projects in Chinese administered Tibet were being restarted. China Tibet News reported on February 29 that more than 2,800 workers had resumed the construction of 338 projects, and by March 3 charter flights were being arranged to bring workers back from the Mainland to Tibet.

Chinese author, Ma Jian

In summing up PRC’s approach to the crisis Chinese author, Ma Jian, believes that Beijing’s “obsessive objective” is the demonstration of its own political system’s superiority, and that “in times of crisis, the Communist party always places its own survival above the welfare of the people”. Amongst Western politicians such as Ian Duncan-Smith this approach may no longer be acceptable as “China seems to flout the normal rules of behaviour in every area of life – from healthcare to… internal repression”, and “once we get clear of this terrible pandemic, it is imperative that we all rethink that relationship [with China] and put it on a much more balanced and honest basis”.

Print

Print Email

Email