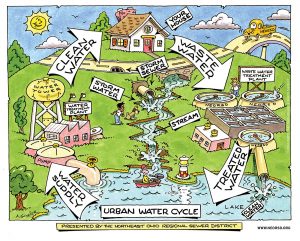

Figure 1

Access to water is precious. And its quality is just as important as its quantity.

Depending on water and waste treatment, we can either have a “healthy” or an “unhealthy” stream. Water from streams is usually treated to guarantee that it is safe “clean water” [Figure 1]. Unsafe drinking water is still a serious problem in Dharamshala and all over India and can be caused by two factors:

•If people cannot access to treated water and depend on water that is not treated effectively. Maybe even waste water.

•If people’s water supply becomes polluted, for example by poor quality supply during the monsoon season.

The Dharamshala-based non-government organisation Lha Charitable Trust has helped in both cases by installing 25 water filtration systems in the Dharamshala region. Now, nearly 14,000 people are receiving adequate drinking water and a variety of institutions have benefitted from the programme.

But just as important as the treatment of drinking water is the treatment of waste water. The discharged water may become someone’s drinking water downstream – repeating the process in Figure 1. Only effective treatment of waste water can keep the stream healthy. That means:

•Treat toilet water (black water) in a sewerage plant. These are preferred in developed countries because they are more reliable than private home septic systems. Dharamshala region has a sewerage plant at Jawahar in Gulerian, just a kilometre south of the Dharamshala cricket stadium – but remote houses may still use septic systems.

•Treat water from sinks, showers and clothes washing (grey water). In most developed countries grey water is treated together with black water. In McLeod Ganj, and many areas in India, grey water is discharged to the environment, polluting nearby streams.

•Treat stormwater (see middle section of Figure 1). Overland flows from rain and snow pick up sediment, rubbish and animal faeces and can cause flooding. In many developed countries sediment is managed, rubbish is placed in bins, animal owners collect faeces, and roof water is harvested. Though Lha helps this with the monthly waste clean-ups there is no government programme to manage storm water.

The Indian government and Lha are improving drinking water quality and waste water treatment. Still the situation is far from ideal as about 40% of Indian children suffer from physical and cognitive stunting due to a lack of safe sanitation.

The Indian government and Lha are improving drinking water quality and waste water treatment. Still the situation is far from ideal as about 40% of Indian children suffer from physical and cognitive stunting due to a lack of safe sanitation.

Luckily, the water quality in rivers in Himachal Pradesh is quite good. But to keep it that way and further improve the local streams, communities have to work together. Especially because poor quality water impacts on people downstream. To help those in Dharamshala and on the Indian plain, those living in McLeod Ganj should follow Lha’s brochure Keep Your City Clean and Green: Don’t throw garbage on the ground or Repair water leaks.

The result of this and advocating for grey and storm water improvements would be better water quality leading to healthy streams and happy people.

Print

Print Email

Email