Tom Barr

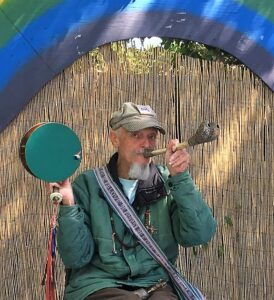

In 1995, an unassuming American man named Tom Barr moved to Dharamshala. Tom had been practicing Vajrayana Dzogchen Buddhism in the United States since the 1970s and living in Nepal for years. Yet after meeting his guru, Ngakpa Karma Lhundup Rinpoche, it was clear he needed to relocate to India to deepen his practice.

Tom moved into a small and simple room near Karma Lhundup Rinpoche’s house and next to the Rigzin Namdolling Ngakpa Gonpa, a small monastery whose name was bestowed by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. This is the place Tom would live for over two decades and from where he would transform the Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV) school system.

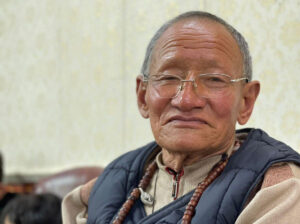

Today, a small group gathers in the home of Karma Lhundup Rinpoche to remember Tom, and his friend Phuntsok Namgyal, over a beautiful meal prepared by Karma Lhundup’s wife, Dawa Dolker, who welcomed Tom into their home during his decades here.

“Tom ate every meal at this table,” Karma Lhundup Rinpoche says, remembering Tom, who became part of his family. “And Tom never complained,” he went on, reminiscing about their many pilgrimages to Buddhist sites around India. On a limited budget, they slept at modest guest houses and ate sparingly. Tom was perfectly content, a quality Karma Lhundup Rinpoche admired. “He would rather take a public bus for hours than a private taxi.”

Soon after they met, Karma Lhundup Rinpoche recognised Tom’s extraordinary mind; he had been acknowledged as a child prodigy from an early age. Though modest, his close friends knew he was sharing discoveries with the world’s foremost mathematicians. Those who knew him acknowledged his gift as a meticulous recordkeeper. One such example is a spreadsheet of his practices, a colorful bar graph entitled “Mantra Counts.” The document, found after his death, details his practices of Tibetan Buddhist mantras totaling 100 million from 1970 to 2021.

Soon after they met, Karma Lhundup Rinpoche recognised Tom’s extraordinary mind; he had been acknowledged as a child prodigy from an early age. Though modest, his close friends knew he was sharing discoveries with the world’s foremost mathematicians. Those who knew him acknowledged his gift as a meticulous recordkeeper. One such example is a spreadsheet of his practices, a colorful bar graph entitled “Mantra Counts.” The document, found after his death, details his practices of Tibetan Buddhist mantras totaling 100 million from 1970 to 2021.

“Tibetan Buddhism was the first practice in Tom’s life that challenged him,” said a dear friend of Tom’s, “He was truly a genius.”

In 1997, Tom was introduced to the director of a Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV) school at Gopalpur, General Phuntsok Namgyal, who joined TCV in 1975, 15 years after its ,establishment. Phuntsok Namgyal was a formative presence in the development of TCV, recognised for his warmth.“ He sincerely cared about students’ well-being,” said former Lha Director Dorji Kyi, reminiscing on Phuntsok Namgyal’s personal visits to students’ homes. “When his students did well, he always made them feel how proud he was.”

Tom with Ngakpa Karma Lhundup

Karma Lhundup Rinpoche remembers Phuntsok Namgyal’s humour recalling, “When Phuntsok Namgyal heard about Tom’s offer to volunteer, he said ‘It must be one of those hippies!’” But after they met, Phuntsok Namgyal approached Tom personally and regarded him as a godsend and a lifelong bond between the two men was forged. They became the best of friends, communicating almost daily for 25 years. Together, Phuntsok Namgyal and Tom established a much-needed TCV resource: a computer system sophisticated enough to organise operations and records for tens of thousands of students and teachers. Soon after they developed the system, which transformed and streamlined TCV operations, staff joked that wearing pen drives replaced wearing amulets. The system they designed and managed became their “lifework”, echoing Tom’s sentiment that this work gave his life meaning.

Yet all those decades, Tom worked as a volunteer. He would not accept donations or payments; only tea. Twenty of those years were spent in India, often working with Phuntsok Namgyal in person. Even after breaking his hip in 2017, Tom remained in India. Dawa Dolker became his caretaker and she smiles lovingly as she speaks affectionately of her strong bond with him.

Due to complications with his hip replacement, Tom returned to the United States in 2018. He continued working remotely with Phuntsok Namgyal. In April this year, Tom was diagnosed with late-stage cancer and on June 13 Tom called Phuntsok Namgyal to announce his last workday for TCV. He then began his mind-body death meditation practices. He stopped eating and drinking and went deeper into meditation practices each day. He was joyful and his mind was clear.

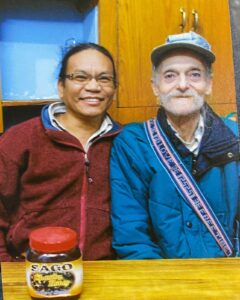

Tom and Ngakpa Karma Lhundup

At the end of that week, on Sunday, June 19, Tom asked his helpers—hospice workers from St Joseph’s Hospice in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA—not to disturb him. During a final check-in that evening, with a nod and smile, he let his close friend Neil know he was fine and that he would be going soon.The following morning Tom’s body was found in the posture of the sleeping Buddha, with his gaze focused on a photo taped on the wall next to his bed of his teacher, Karma Lhundup Rinpoche, with the great Dzogchen Master Sholpa Lama Gyurme Dorje Rinpoche. Karma Lhundup Rinpoche led a day-long ceremony with Tsogyal feast offerings, fire pujas and 108 butter lamp offerings; a 49-day post death puja was performed at a small temple in Nepal by a small group of monks under the direction of Venerable Tsering Phuntsok.

Phuntsok Namgyal died in India about three hours before Tom died in the United States. Phuntsok Namgyal’s obituary called his death a “sudden demise.” Their fortuitously timed deaths mark the spectacular friendship and broad, profound impact of two lives, karmically connected.

Phuntsok Namgyal died in India about three hours before Tom died in the United States. Phuntsok Namgyal’s obituary called his death a “sudden demise.” Their fortuitously timed deaths mark the spectacular friendship and broad, profound impact of two lives, karmically connected.

“The importance of having a lifework,” says a dear friend of Tom’s, “This is one of our greatest lessons from Tom.”

Print

Print Email

Email