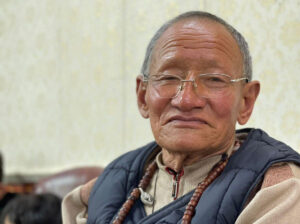

LobsangYangtso is the Asia region campaign coordinator at the International Tibet Network in Dharamshala. She agreed to meet me to tell me about her work, which involves organising climate strikes and raising international and local awareness of issues relating to the Tibetan environment.

Lobsang was born in the shadows of the Minya Konka range in Ganzi, which I know as a place where the sky and the land seem to embrace each other in an eternal dance, the Rongcha river rolls towards its union with the Yarlung, yaks and rocky ridges dot the vivid green hills, and Chinese soldiers and police officers patrol the streets. Lobsang escaped to India in 1991 when she was 8 or 9 years old and completed her education in India with a PhD at Jawalarhal Nehru University in Delhi with a dissertation focused on “China’s Environmental Security Policies in Tibet.”

She is passionate about her country and what is happening there, and is an expert at getting her message across: Frequently referred to as “the Third Pole”, Tibet is on the frontlines of the Global Climate Crisis. It is warming three times faster than the rest of the earth, with rapid glacial ice melt posing a risk to global water security. From exile, Lobsang despairs at the destructive mismanagement of the environment by the Chinese colonialists in Tibet. In recent decades, China’s exploitation of Tibet’s natural resources has gained a head of steam. Copper, gold, silver, lead, zinc, uranium and other precious minerals are extensively mined in Tibet. Polluting mining activities take place close to rivers and in areas of spiritual significance. Nomadic Tibetans are torn from their ancestral land and forced to live in concrete block houses constructed by the Chinese government. Little interest is paid to local objections by native Tibetans as their homeland is sliced open for profit.

Lobsang researches the Tibetan environment using official documents from the Chinese government, including the 5-year plans, studies carried out by Chinese and western scientists and intellectuals in Tibet, social media, and information from NGOs (non-government organisations). She says it is evident that “Beijing doesn’t understand Tibetan topography” and that there is a “huge gap between policy and reality.” She also believes that economic growth in Tibet is of primary importance to the Chinese government and that environmental concerns are given short shrift.

She talks about the vast infrastructure projects completed or under way in Tibet, which include new airports, penetrating road networks, dams, and the Qinghai Tibet railway. These developments will lead to “Tibetans becoming a minority in their own land,” as money hungry Chinese will see economic opportunity in Tibet and move to the roof of the world in search of their fortunes. “Most Chinese politicians are from engineering or military backgrounds,” Lobsang explains, this warps their perspective in favour of infrastructure projects and blinds them to their environmental impacts. “They rarely carry out Environmental Impact Assessments, and when they do, they are not independent from the government, they are corrupt.” Traditional strategies for managing the land practiced for centuries before the Chinese invasion are completely “discounted”.

Lobsang implores Tibetans not to get comfortable with the new normal and to resist Chinese efforts to pacify resistance to their occupation with economic development: “The Chinese see economic development as a panacea for all of the problems they face in Tibet. Economic development has been introduced so that the Chinese can rule the Tibetans. Subsidies are paid to Tibetans to hold them to ransom.” Tibetans must remain alert to this strategy and “keep awareness of Tibet as a free country.”

In 2015, Lobsang attended the COP 21 Climate Conference in Paris. Like many, she had “huge expectations” of a global consensus around combating climate change. At the conference she attempted to explain the significance of the Tibetan environment to the delegates but was frequently left exasperated by their lack of understanding around crucial issues. Chinese delegates refused to talk to Lobsang once they found out she was a Tibetan in exile.

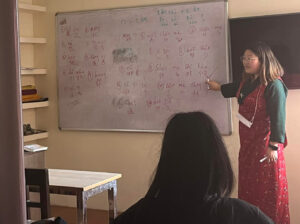

In the years since, Lobsang has come to believe “corruption is inevitable when governments get involved so people and NGOs need to organise for action to resist climate change and not rely on policy makers and world leaders.” This inspires her to organise climate strikes. Everybody should “take the initiative”, she says, “rich and poor need to engage.” On November 29, in solidarity with Climate Crisis Strikes around the world, Lobsang led the Dharamshala climate strike. The message was “The Earth is on fire, and Tibet is Melting – Climate Action Now.”

Print

Print Email

Email