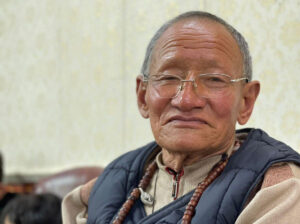

Tenzin Norbu

Photo: Tenzin Dadon / Contact

Blind People live in the world of …………………………

The first word that must have come immediately to the majority of people’s minds would be ‘Darkness’.

I ask why not? Blind people live in a world of ‘sound’, or ‘touch’, or ‘creativity’, or ‘care’, or, most importantly,‘trust’. Clearly when our thinking is blinded by stereotypes and false notions how can our society progress towards inclusion?

“People in our community need to understand that disability doesn’t mean that persons with disabilities are handicapped, there is so much that we can do. If you could just spend a day or two with us, you would definitely see.”

These are the words of Mr Tenzin Norbu who is currently working as an instructor at the Tibetan Handicapped Children’s Craft Centre (Nyingtop-ling, in Tibetan) at Sidhpur in Dharamshala. Mr Norbu has partial visual impairment by birth and as his age grew so did his trouble with vision. He says he can’t remember having a father but at the tender age of 13 years old he lost his mother. His only sister started working at a carpet factory in Nepal after their mother died.

Norbu started going to Namgyal primary school in Swoyambhu, Nepal and did his schooling up to sixth grade. Reading became difficult without proper assistive devices and he decided not to go for further study. Fortunately for him Mrs Rinchen Khando (the sister in law of His Holiness the Dalai Lama) while visiting the school came to know about Norbu and admitted him to the National Institute for the Visually Handicapped (NIVH) in Dehradhun. It was at NIVH that Norbu learnt chalk making, candle making, chair caning and various other skills. While at NIVH he was inspired to learn Braille from Mr Tsewang, his vocational teacher, who has complete visual impairment himself. Norbu says it’s a shame that he has forgotten Braille after all these years because it is never used in Tibetan society.

After working for seven years – making chalk for schools – at a Vocational Training Centre in Mussoorie which was under the administration of Tibetan Homes Foundation, he came to Dharamshala. He wanted to live an independent life. With seed money of INR 50,000 ($780; £600) from the Department of Finance at the Tibetan Government-in-Exile, he started a prayer flag selling business. He used to sell prayer flags outside the Temple gate or gate of the Library at a minimum profit of Rs 10 (15 cents; 12 pence) for each set of five flags that he sold. When his partner (an elderly lady or Amala as they are called in Tibetan) died he had to give up this business as it was really difficult for him to do the cutting, printing and stitching as well as selling the flags. After staying jobless for some time, he heard about a vacancy at the Tibetan Handicapped Children’s Craft centre. He applied for the job and is particularly proud of his appointment there because he did not use his family connections – as so many people do – to get the job. He wanted to do it on his own merit alone and feels this is an achievement which shows that a person with disability can have high aspirations and self esteem.

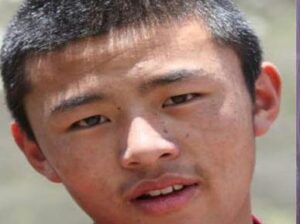

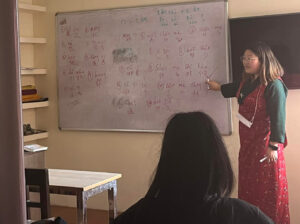

Norbu with one of his students

Photo: Tenzin Dadon / Contact

Norbu is now 49 years old. He started working at the institute with a monthly wage of INR 1,000 ($15.5, £12), and continues still with a minimal wage now of about INR 5,000 ($78; £60). But he says there is so much satisfaction in his job which has nothing to do with the administration – his students are his sole inspirationand this is what keeps him going. Everyone loves him there. He says that all students there are different and he knows how to carter to the needs of each one of them. “You just need to understand them, get to know them”, he says.

At Nyingtop-ling some children and young adults have physical impairments which are visible, but it is difficult to understand the others who have metal impairment. Throughout their life they have been treated as being mad or as though they are a vegetable,and thus are neglected.In Tibetan society, a stereotype which is still so prevalent is that mental impairment is equivalent to being ’MAD’ which is not true and thus many parents try to hide their children and opt for segregation rather than inclusion,fearing this label.

It was under Norbu’s initiative that a separate activity of candle making was started in the institute. He feels that it is a shame that this activity is only regarded as a source of income at the time of Gaden Nyamchoe – the anniversary of the deathof the great Buddhist Scholar Jhe Tsonkhapa – when everyone lights candles and offers butter lamps in the evening as a symbol of brightening his path. Usually candle making is not given so much importance at the institute or included in the daily schedule. Norbu feels that people with disabilities are still considered a charity model in our community. He feels that there should be a proper class schedule and some form of assessment to test the progress of these students so that we can make these young adults independent and self-reliant.

It is high time that our community should have proper assistive devices and start heading towards inclusion. Inclusive schools and inclusive employment opportunities are a must.“Empower us”, says Norbu,“for we too are productive members of this society”.

Print

Print Email

Email