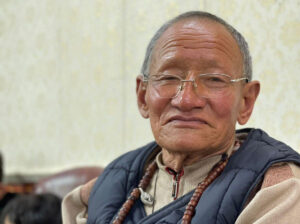

Youdon with her son Namdak

Youdon passes easily through the pell-mell of people in McLeod, one hand holding onto her five-year-old son, the other gesturing for me to follow. She skips over cowpats, picking her way around potholes and roadside stalls as though she’s done this trip every day for a long, long time.

And she has. India’s been Youdon’s home for 15 years. She ran away from Tibet when she was only 18, sneaking out in the middle of the night and leaving her brothers, sisters, mum and dad behind. She hasn’t seen them since.

“My parents would never have let me go,” she explains, “but I wanted to experience the real world. Growing up, armed Chinese policemen patrolled my village and I never understood why. My father would tell me stories about two great tribes — one peaceful, the other power hungry, but never more than that. Everyone knows that walls have ears in Tibet.”

We have arrived at Youdon’s home, one of the many in McLeod teetering precariously on the mountainside. They are stacked like playing cards, as if one day, a sharp gust of wind will simply blow them all away.

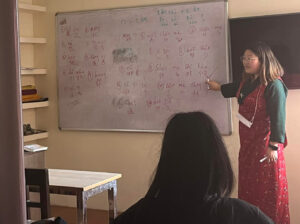

It’s to be my home too for the next ten days, and Youdon tells me her story as I sip Tibetan butter tea, cross-legged on the floor. The kettle hisses on a camping cooker, the Dalai Lama smiles down on us from a poster on the wall and through the window, monks gather, their robes falling around them in crimson waves.

Youdon’s journey across the Himalayas took 22 days; walking all night, snatching a few hours sleep when the sun rose, and praying continuously that Chinese guards didn’t spot her, or their dogs smell her. It was terrifying, she admits, but she was one of the lucky ones. She reached Nepal before the weather turned — frostbite claimed the fingers of those three days behind.

As I listen, engrossed, her son Namdak vies for my attention, all shyness evaporated now we are on his turf. He is beautiful in the way exotic children are: rosy-cheeked, with eyes the shape of almonds, and we communicate via a “he points, I draw” system. My attempts at pictures from his schoolbooks are scoff-worthy (which he does, wagging his finger and shaking his head).

His father is conspicuous only by his absence. He’s been in France for almost four years, trying to get refugee papers so they can buy a place over there. It’s almost impossible for Tibetans to own property in India, and many of them wouldn’t want to, resolute in their belief that a return to their homeland is on the horizon. But many others are moving away, wanting finally to lay down some roots.

“No one sees McLeod as home,” Youdon tells me. “The Indian government is very kind, but even those who were born here, even those who fled Tibet as long ago as 1959 with the Dalai Lama look at this as a temporary set-up. Of course, I still hope to go home, but while the country is occupied I couldn’t even if I wanted to. When I left, I did so knowing I would never be allowed back.”

Temporary or not, Tibetans have made themselves a life here. When Youdon first arrived in McLeod, fresh produce was almost impossible to find. Now, mounds of rainbow-coloured fruit flank the streets. Schools and temples have been built, they have their own government-in-exile, and a five-minute stroll down the hill takes you to the Dalai Lama’s doorstep. It’s a refuge — a sanctuary for a displaced nation.

And success at last — I draw a passable imitation of Sponge Bob Square Pants, making Namdak squeal with delight. I smile back, simultaneously happy and sad, wondering whether one day Tibetans will be dealt a different hand — whether one day they’ll be able to go home, their playing card houses left behind in McLeod.

Print

Print Email

Email