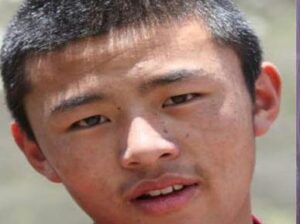

Tenzin Tsundue always knew he was different. He was marked, his teachers told him, branded with a huge red R on his forehead. R for refugee.

Tenzin Tsundue always knew he was different. He was marked, his teachers told him, branded with a huge red R on his forehead. R for refugee.

“I felt like superman. Only we Tibetans had it and it meant that our lives were not for ourselves but for a greater cause, a huge cause; we were there for Tibet.”

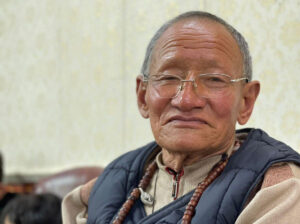

It is a feeling that has never left him. And the imaginary R has become a red bandana that Tsundue refuses to remove until Tibet is free.

He grew up in a tiny boarding school in Himachal listening to tales of an idyllic homeland. From the playground he could even see the snow-capped mountains behind which Tibet lies.

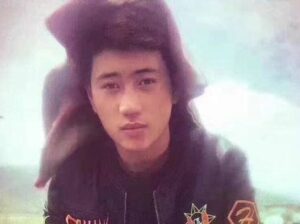

“It became a kind of secret dream,” he says wistfully, “a romantic ideal that even though I have been to Tibet I still have now. I was 22 when I made the journey, a fresh college graduate. I had a degree in English Literature from Loyola College in Chennai and a job teaching in a Tibetan school.

But I was tired. Tired of protesting against the Chinese on an Indian roadside, tired of sloganeering. I wanted to do something, to face the real enemy. I think at that age you are your own hero. You feel so very brave, invincible almost. So at a time when a huge number of people were escaping the country, I did the reverse. And I did it alone.”

Tsundue walked 400km across the Himalayas. He survived for five days in the Tibetan desert without food or water, and then, after encountering the Chinese, endured a further three months in a prison cell with little more.

“I was suspected of a spy mission, starved, interrogated and tortured” he recounts. “I thought it was the end. I lived in constant fear that I would die there and nobody would know.”

That was Tsundue’s first time in prison. He has been detained 17 times since and describes the experiences sardonically as “educational.”

At 28, a young and restless activist,he scaled a building and unfurled a 50ft banner emblazoned with the words: “Free Tibet: China, Get Out.” It hung defiantly opposite the hotel where the Chinese Prime Minister, Zhu Rongji was staying in Mumbai. Despite an arrest and a travel ban he staged a similar, equally spectacular demonstration a few years later, this time in Bangalore.

His solo protests have secured him columns in newspapers, a privilege, he states bitterly, that his countrymen barely even achieve by burning themselves alive. For Tsundue, however, equally important to the freedom struggle is art.

“People trust art where they don’t trust politics. So I write. When I am writing I am a poet. But when I publish I am an activist. I write because I have to, because my hands are small and my voice goes hoarse. Writing to me is not luxury; it is a necessity. The writer and the activist live together in me, hand in hand.”

Tsundue’s pen is never idyll, and with three books already under his belt he is soon to release a fourth. The first, Crossing the Border, was only made possible by contributions from university classmates and earnt him the prestigious Outlook-Picador Award for Non-Fiction in 2001. Kora, a collection of poems and short stories is in its eighth edition and his new venture, he says excitedly, will intertwine the inspirational stories of those around him into a web of Tibetan lives.

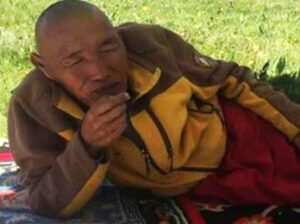

He describes himself proudly as a minstrel: a travelling entertainer and an ancient tradition in Tibet. With the money made through book sales Tsundue tours universities, teaching students about the idea of exile, how refugees cope and how having no home shapes your identity.

“It makes you strong,” he states, “able to bend with the wind and not break. For me, my activism is a different kind of struggle. I don’t have to kill anyone but it is a big thing for a refugee to try and transform people’s outlook. Through my poems and stories I attempt to change minds, to teach the public about what is happening in my country. Only when they know will the policies of government change.

That is my role. But I think that whoever you are, whether you are a monk, a teacher or a banker, as Tibetans, we all must play our part.”

R may stand for refugee but Tsundue knows that what it truly means is responsibility. A duty to hope, a duty to fight, a duty to never give up on Tibet.

Print

Print Email

Email