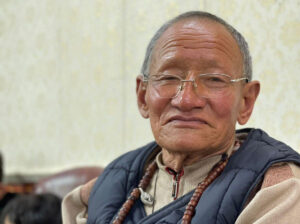

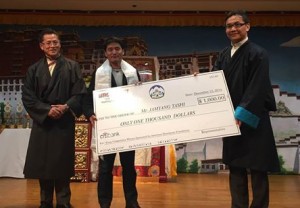

Jamyang Tashi’s prize-winning essay entitled “One of Seven Billion Human Beings” is reproduced below. It won the prestigious $1,000 first prize in an essay contest initiated by the Office of Tibet, Washington DC, to commemorate 2014 as the Year of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The contest was open to all Tibetans residing in North America between the ages of 18-35, and was sponsored by The American Himalayan Foundation.

Representative Kaydor Aukatsang congratulated Jamyang Tashi and awarded him the prize during the 25th Anniversary of the Nobel Peace Prize celebration with the New York and New Jersey Tibetan community in New York.

One of Seven Billion Human Beings

by Jamyang Tashi

“What does the Dalai Lama mean to you?” One of my American friends asked me this question about two years ago after we had a long conversation about the self-immolations inside Tibet that had reached media attention all over the world. My instant answer to my friend was: “It’s going to take a long time to talk about him”. It wasn’t an attempt to avoid answering but rather to see if he would be willing to listen to me explaining such a renowned person in my imperfect English. My answer had doubled my friend’s curiosity. He jerked forward and expectantly said, “Please, I have nothing but time”.

I realized that I had misunderstood his question. He wasn’t asking me to talk about the Dalai Lama. He wanted to know how I felt about the Dalai Lama. Oddly this was a new question to me. I began noticing the difference between telling who the Dalai Lama is and explaining what he means to me. I immediately found myself in a situation I had never been in before. To explain what the Dalai Lama meant to me didn’t seem to require knowing any of his biographical data but to recall my own life. At this point the question had become personal and I became very emotional, and couldn’t say anything while my friend was staring at me. I felt embarrassed not having an answer after I had told him that I had a long answer to his question. At the same time, I was getting worried that he was going to notice my internal struggle to hold down the stirring emotion that might burst out from my eyes. I can’t remember how long I had paused but at some point my friend said: “It’s ok. I think I can guess how much he means to you”. Part of me was relieved, but his question remained with me. What I am going to say below is a very common experience shared by thousands of Tibetans, and so if I had a purpose in writing such a common story, it would be for my non-Tibetan friends who are so curious about why I am so attached to His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.

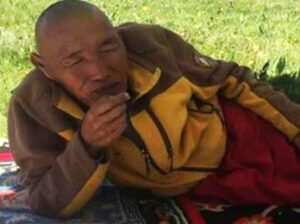

I was born and raised in a remote village in Tibet, in a family in which none of the members had either seen the Dalai Lama in person or heard his voice. The only physical representation of the Dalai Lama in my house was an 11×13 portrait of him. Yet, as far as my memory stretches, the Dalai Lama held the preeminent authority in my household. The day’s adventures were entrusted to him every morning. Family issues were solved in his name, and misbehavior was forbidden in front of him. And he got the best portion of every little feast shared in my house. In the mind of a child in that house, the Dalai Lama sometimes seemed like a fictionalized gentle king who ruled everything without having to say a word. But looking back, he was the riverbed that shaped the current of my family’s life.

Gyalwa Tenzin Gamtso is the name we use for the Dalai Lama in my region, and I often wonder if these three words were the first I ever heard. I remember the first time I saw the Dalai Lama’s face. It was a night I was so sleepy and was waiting for my mother to accompany me to bed. But it was taking her so long to finish praying. Despite my growing impatience, the tone of her voice uttering incomprehensible words and the seriousness on her face were something that I had no courage to complain about. For some reason I still don’t know, I went and stood next to my mother, and facing toward the altar, I held my hands together in the way she was holding hers. She dropped on her knees and taught me how to say, “Gyalwa Tenzin Gamtso”, and after I was able to repeat them, she taught me how to do three prostrations toward the picture of a smiling man in the altar. From that night on, I was able to identify that smiling man as Gyalwa Tenzin Gamtso, and no matter from what direction I looked at him, he was always looking at me with an affable smile.

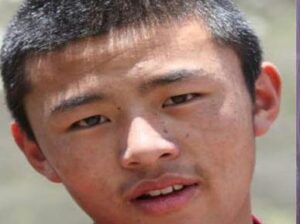

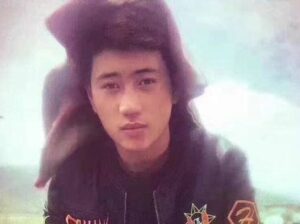

Growing up in Tibet as an illiterate young man and having no access to anything beyond the mountains surrounding my village, sometimes I was caught between two definitions of the Dalai Lama. According to my family and other Tibetans, the Dalai Lama was no less than god. But based on what I heard from Chinese officials, he was nothing more than a power hungry fake monk, and sometimes they even described him as a monster. Of course I trusted my family and Tibetans. But as a coming of age teenager, I once did wonder what if the Chinese officials were right. I was ashamed at having such a thought in my head. But looking back, I am thankful for having had that thought because it was part of the reason I decided to leave Tibet for India to see the Dalai Lama myself. From the day I set out on my journey toward India when I was eighteen, every day was a reminder of moving further from my beloved country, but each step I was taking was a reminder that I was getting closer to the Dalai Lama.

Upon reaching India, I had my first audience with the Dalai Lama along with over sixty other Tibetan refugees. As we all gathered at the gate of his residence, a security guide led us to a porch where we all sat facing a red armchair. All of us in the audience shared one feeling–none of us really knew whether it all was a dream or real. I knew the Dalai Lama was going to sit on that red armchair, but behind that chair there were two doors left open and I didn’t know from which he would come out. A few minutes before he showed up, there was such a deep silence that it seemed no one was even breathing. Then suddenly he rushed out from the left door, almost running toward us. The moment I had waited for my whole life was shining in front of my eyes. Yet his face was no different from the picture I grew up with in my house. All of us in the audience burst into tears for at least a few minutes and the whole time, he was standing in front of us repeating, “Don’t cry, now we are together”.

“I am happy that you all got here safely”, he said as he started his half an hour talk to us. Although he spoke a different dialect that I was not used to, I didn’t feel I was missing anything he was saying. Sometimes in order to feel everything you are being told, you don’t have to understand the meaning of every word you are hearing. First he talked about the importance of education in the modern world and then, he went on talking about how to be a good human being. He concluded his talk on how to combine education and a good attitude in order to serve society. He spoke with such clarity that I sometimes felt I could hear every letter of the words he was using. Although he was talking to over sixty people, every one of us felt he was talking to us individually. The feeling every one shared after we met him was that we were reconnected with our long lost father.

I went home feeling transformed. The Dalai Lama was neither the god that I had imagined with my family, nor the monster that Chinese officials described. He is a real monk who practices love, compassion, tolerance, and forgiveness. He is a teacher who teaches on how to give. He is a scholar who learns everything through investigation and delivers every thought with reasons. He is a leader who wants to do everything he can to pay off his people’s love and devotion to him. He is a visionary who envisions his country as a zone of peace that would radiate to the rest of the world. He is a master on the functionality of mind. He is a student who studies the equation of E=mc2. He is a human being who will be remembered by the last historian of humanity on this planet. To best of my knowledge, this is the Dalai Lama of whom I am fortunate to be a follower. Following his teachings I try to learn how to love everyone equally, even those who destroy my country. Under the light of his guidance, I lift my head and am trying to look into the horizon. Because of his reputation, I find it comforting to introduce myself as a Tibetan.

Jamyang Tashi was born and raised in Thewo, Amdo, in Tibet and escaped to India when he was eighteen. He is currently studying filmmaking in the City University of New York.

Print

Print Email

Email